Dr Seuss books are getting canceled and I couldn’t be more envious. Earlier this month, the Seuss estate announced that it would discontinue publication of six of the author’s beloved children’s books after consulting with shrieking activists. The reason was that some of their illustrations depict blacks and Asians in offensive and outdated ways. From there, the flimsy dominoes of corporate America began to fall: eBay banished the titles from its online store; Universal Orlando announced it was ‘evaluating’ the theme park’s Seuss Landing area.

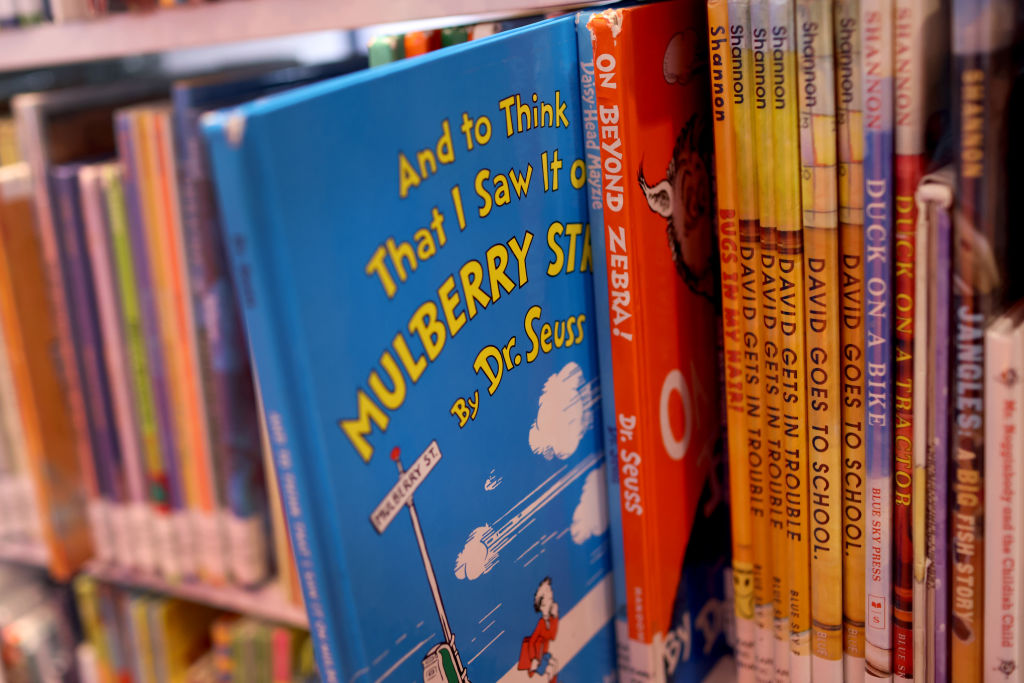

All this is bad news for one of America’s most imperishable literary icons. Still…have you seen those book sales? In the first week of March, the top 10 children’s books on Amazon were all by Seuss, as were 23 of the top 30. The dirty half-dozen that were banned are still available for purchase but subject to the laws of supply and demand: at the time of writing, a hardcover of And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street will run you $300; Scrambled Eggs Super!, one of the lesser known titles, starts at $923. And this is before the blackmarket kicks in. One imagines gangsters shooting at each other out of car windows over copies of If I Ran the Zoo, Al Pacino sitting at a desk flanked by Thing 1 and Thing 2.

Apparently getting canceled can be lucrative — and I’d like my cut. The problem is, I can’t seem to get arrested in this town.

In fairness, unlike Seuss, I have yet to write a single book. I plan to one day, albeit probably about politics or foreign policy rather than green eggs and ham or pocket wockets. And when I do, I’d prefer that it sell for closer to $1,000 than $12.99. I’d also love to have it sheathed in that forbidden mystique that comes with a cancellation. There’s nothing sexier than violating a taboo, which is why Dr Seuss books are in such high demand and why woke censorship ultimately contains the seeds of its own destruction. Yet before it collapses under its internal contradictions, I’d like to make a killing. And in order to do that, I need to find a way to get myself canceled.

How to go about this? One obstacle is that cancel censors tend to be like those idiot guards in video games, patrolling theirown cultural hallways while ignoring the conservative periodicals in whose vineyardsI labor. My full-time job is at a magazine whose right-leaning views are subtly alluded to in its name: the American Conservative. So no go there.

One possibility would be for me to get picked up by a more mainstream American publication, whose woke editors could then comb through my work, find something offensive I said 15 years ago, and bang-o, instant cancellation. That’s what happened to conservative writer Kevin Williamson, who was hired by the Atlantic and then fired less than a month later. But right now there just aren’t any takers; even Jezebel won’t take me on. It seems that if I’m going to get canceled, I’ll need to manufacture a scandal on my own. This seems, at any rate, like the American thing to do. In this land of rugged individualism, we need to be entrepreneurs of our own micro aggressions. The last thing we want is to start outsourcing our braindead moral panics to other countries.

To begin my self-cancellation, I decide to try a dry run on my Spectator editor, Freddy Gray, who lives in the UK. I type up a text to him: ‘There are only two genders.’ Then, deciding that’s too extreme, I change ‘two’ to ‘14’ and press send. His response: ‘You know it’s three in the morning over here, right?’ He refuses even to screenshot my text and tweet it at the Huffington Post with a GIF attached of Tina Fey rolling her eyes. Instead he says something offensive about the Scottish and begs off.

Hope springs for my auto-cancellation the next morning. Making my breakfast, I realize I may as well be at a neo-Nazi rally. My coffeemaker is manufactured by a company called Mr Coffee, which outrageously assumes the gender of millions of plastic filtration baskets. My maple syrup is Aunt Jemima brand, which canceled itself last summer for featuring an African American woman on its bottles. My butter is Land O’Lakes, whose logo was once an Indian maiden. Only my cereal, Lucky Charms, is not yet known to have received any complaints. I arrange all these items on my table, take a picture, post it on Instagram and generally undermine civilization as we know it. Yet my friends refuse to bite. One bigot replies, ‘You should make English muffins too!’

Feeling dejected, I decide after lunch to head down to my local bar. Maybe a few drinks will spur me to do something truly transgressive, like watch The Muppet Show with the windows open. I sit down at the counter and order a Sam Adams, one of my favorite beers, only to realize I’m quaffing the nectar of a cisgendered white man who appropriated Native American culture to throw British tea into a harbor. My eyes are then drawn to the draft spouts and I recoil in horror. Raging Bitch IPA. Golden Monkey Ale. Union Jack IPA. A glance at the liquors reveals more terrors: a Redbreast 12-year, as well as a handle of Beefeater, which must be offensive in some way.

And then I look out the window and Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ crashes in my head. A child is walking past with a Harry Potter book under her arm.

And that’s just it right there. Try though they might, they can’t cancel us all. America’s two most innate tendencies, capitalism and moral panic, have been pitted against each other — and while the fight is still on, while the latter has in some ways commandeered the former, capitalism seems destined to triumph in the end. There’s simply too much culture, too much product, to erase everything that doesn’t measure up to some capricious pencil mark. Cancel culture is real and it poses a threat to free expression. But it’s also largely the bailiwick of sad Twitter activists, intersecting with the real world less often than we think. And even when it does, there will always be those who love nothing more than to poke a thumb in the eyes of the dreary and the literal-minded.

As I walk home, I gloomily admit that I’ll probably never be canceled. Time for Plan B: trying to get an ‘environmental justice grant’ from the stimulus package.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.