Ross Perot, who has just died at age 89, is wrongly remembered as the man who cost George H.W. Bush his re-election in 1992. He should be remembered as the man who cost his own populist ideas their chance to remake American politics 20 years before the election of Donald Trump. Perot showed the promise of populism — then betrayed it, bottling it up for the next two decades. As far as Perot was concerned, if populism could win without him, it shouldn’t win at all. And so he made it as difficult as possible for anyone else — Jesse Ventura, Pat Buchanan, and yes, even Donald Trump — to build on what Perot achieved in 1992.

And maybe Perot did cost Bush I his re-election, just not in the way most people think. Polling suggested that Perot pulled about equally from voters who would otherwise have cast their ballots for Bush and those who would otherwise have voted for Clinton. But Perot had inflicted his damage on Bush long before election day. Bush I was the first post-Cold War president, and he faced a choice between maintaining an internationalist economic policy that had been in large part a strategy to prosecute the Cold War — adding partners to the US power bloc — or adopting a new policy aimed at keeping jobs in America rather than seeing them relocate to East Asia or Mexico. Bush chose internationalism. This left an opening for someone else to champion the American worker — a role for which Pat Buchanan auditioned in the Republican primaries, and one that Perot elected to play in the 1992 general election. He had competition from Bill Clinton, however, who also campaigned as a populist of sorts — ‘I feel your pain’ — but whose program was, at that time, more of a traditional Cold War liberal welfarist agenda.

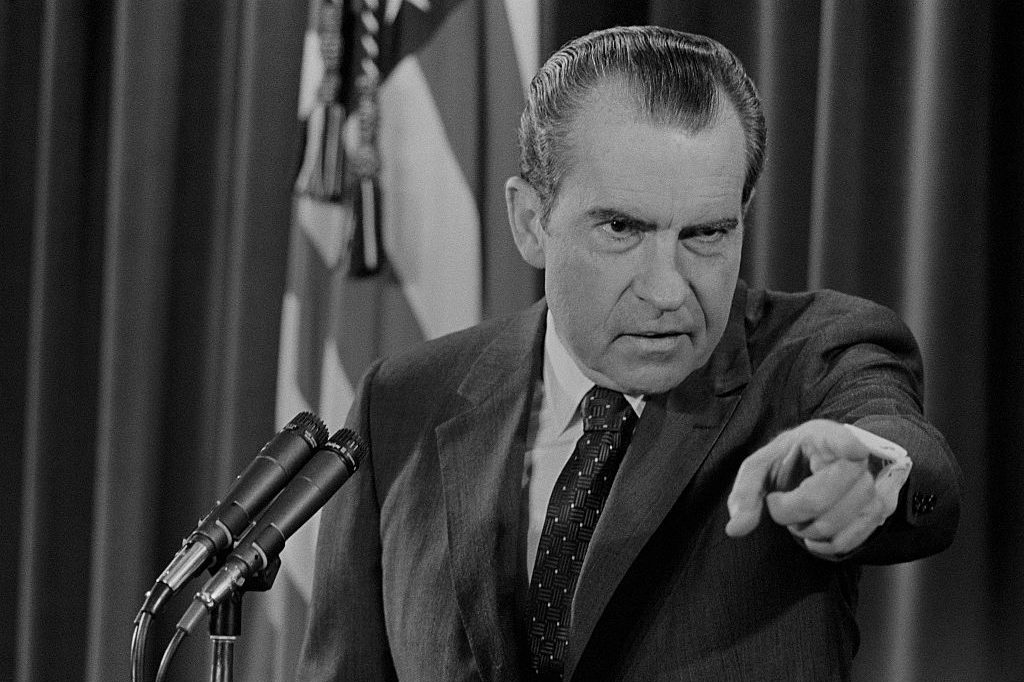

Nevertheless, Perot provided a contrast with Bush that showed the Republican party was no longer the party of the ‘hard hats’ who had been indispensable to Nixon’s ‘Silent Majority’ and who were the essential ‘Reagan Democrats’ of the 1980s. Bush’s Republican party was not a workers’ party. Yet Perot also showed that it was not a party of fiscal discipline. Though Republicans continued to talk about balanced budgets, and even mooted a constitutional amendment to guarantee them, in practice the GOP was the party of deficits, and cutting taxes took priority over balancing the federal government’s accounts. Since George H.W. Bush had actually raised taxes, however, the GOP was reduced to absurdity: a big-spending, tax-hiking, fiscally incontinent sham. Again, Perot’s message highlighted the ugly truth.

And Perot touched a raw nerve — especially for Republicans — in foreign policy as well. Before becoming a presidential candidate, Perot’s most notable political commitment was a campaign to discover and free American prisoners of war still held by Vietnam. ‘POW-MIA’ flags were common sights at patriotic events back then. The evidence for remaining POWs was slight, but Americans felt their government had profoundly betrayed the nation’s soldiers. The POW issue was an extension of that. The apparent success of the 1991 Persian Gulf War had not dispelled the psychological ‘Vietnam Syndrome,’ and the GOP, as the party that made claims to superior patriotism and support for America’s troops, had a special burden here. If Republicans wouldn’t take up the POW cause, who would? What good was the GOP if it was as shy about this issue as the Democrats were?

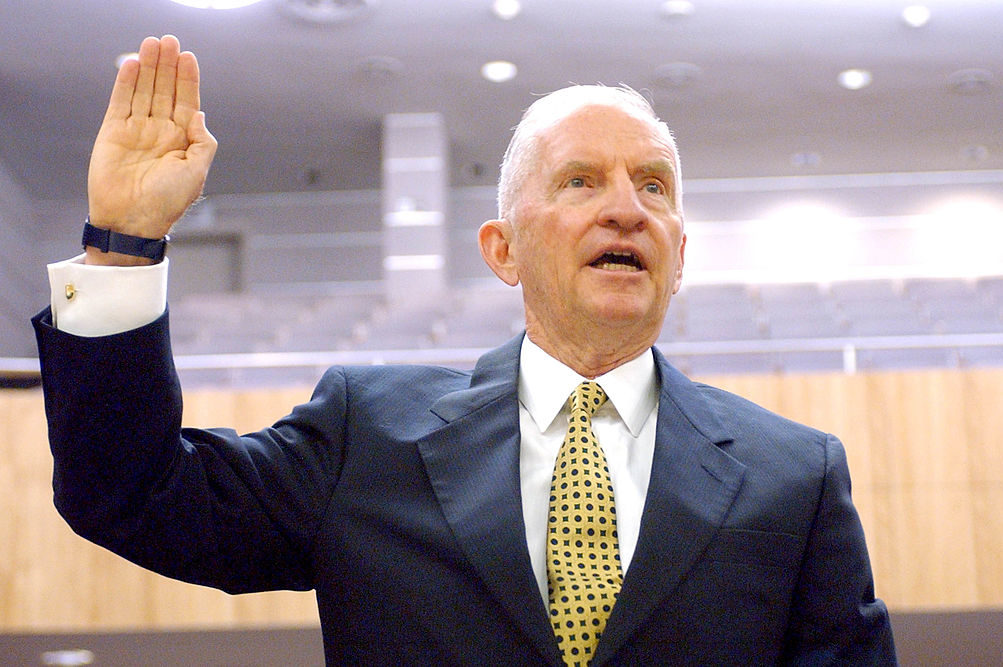

Perot made the Bush GOP’s commitment to the men who fought America’s wars look shifty and unreliable. He also showed how hypocritical America’s media elite could be about veterans. Contrast the media’s shameful treatment of Perot’s 1992 running mate, Vietnam veteran Admiral James Stockdale, with the sycophantic treatment later accorded to John McCain. Both men had been tortured as POWs, and Stockdale was singled out for especially cruel treatment because of his intransigent defiance — he would mutilate himself and even attempt suicide in order to prevent the Communists from using him for propaganda purposes. Yet Stockdale was ridiculed after he was chosen as Perot’s running mate, particularly for asking philosophically at the start on one vice presidential debate ‘Who am I? Why am I here?’ and for turning off his hearing aid for a time while Bush’s and Clinton’s running mates — Dan Quayle and Al Gore — were talking. If valor is what McCain’s admirers respect, they would have to honor Stockdale above virtually anyone else. That wasn’t the way it was in 1992, and it hasn’t been the way since.

So Perot put the lie to the GOP’s claims to be the party of the Silent Majority, the Reagan Democrats, balanced budgets, and honor for our dishonored veterans. He did, to be sure, stake out ground as a middle-of-the-road liberal on social issues: he was for abortion rights but not for the counterculture. This could have cut into Clinton’s support by highlighting his party’s weakness in the same way that Perot exposed GOP contradictions. (In 1992, the Democrats were already almost uniformly left-wing on social issues, and notably denied anti-abortion Pennsylvania governor Bob Casey Sr. a chance to speak at that year’s national convention, but the party was also afraid of association with the counterculture of the Sixties and Seventies.) But the Bush GOP had its own contradictions on social issues, as the party of both the Religious Right in full bloom and the party of business interests indifferent or hostile to a social conservative agenda. In those days it was still a fight every four years over the language of the abortion plank in the GOP platform.

Perot’s allergy to social conservatives was one of the things that would doom his populism and prevent it from becoming a movement at the time when American most needed a national alternative to the Democrats and Republicans, twin parties of free trade, mass immigration, and foreign conflicts. But in ’92, he and Stockdale took nearly 20 percent of the popular vote, a success outstripping anything that a candidate outside the major parties had achieved since the days of Theodore Roosevelt. Perot could have widened that success into an institutional force in American politics, if he had been willing to build a coalition with figures such as Pat Buchanan who agreed with him on most of his signature issues. Perot instead turned the Reform party that he built after his 1992 run into a personal plaything. He frustrated activists and organizers in the party in 1996 by giving mixed signals about his willingness to run again, and when he finally did so he disappointed at the ballot box. (Perot had shown flaky tendencies even in ’92, when he withdrew from the race at one point, only to re-enter it in time for the election, having, however, made himself look ridiculous by his vacillation.)

Buchanan had bloodied George H.W. Bush in the 1992 primaries and, having won the New Hampshire primary, came close to knocking Bob Dole out of the race for the 1996 nomination. But when Buchanan showed interest in running for the Reform party nomination in 2000, Perot worked behind the scenes to block him. The result was to turn the party into a farce, with a faction of Transcendental Meditation enthusiasts aligned with the fringe Natural Law party contesting the nomination with Buchanan. The Republican renegade won, but by the time he did so, not only was the nomination worthless, so was the Reform party itself. Had Perot backed Buchanan or simply stood aside and let him succeed, the Reform party very easily could have been the determining factor in the 2000 election—which of course came down to a handful of votes in Florida, or, depending on your perspective, a single vote in the United States Supreme Court. The Reform party could not have won the 2000 election, but it could have shown that populism was a force neither party could afford to ignore. Instead, thanks to Perot’s hostility to Buchanan’s social conservatism, Perot made his party and Buchanan both seem like proof of populism’s irrelevance. The upshot was eight years of Bush Republicanism in the White House characterized by exactly the sorts of policies Perot had entered politics to run against.

Trump entertained a Reform party run in 2000 himself, and perhaps to satisfy Perot, as well as because of bad advice from consultants, Trump denounced Buchanan at the time. But Trump had the good sense not to seek the nomination of a party whose founder preferred to see it die than have a life after him. Instead, Trump learned from the failures of Perot and the Reform party. Trump, like Perot, campaigned as something of a moderate on social issues — but he did so without excluding social conservatives, and since becoming president he has served his coalition allies better than many a professed true-believer conservative Republican ever did. Trump also realized, as Perot should have recognized a quarter-century earlier, that third-party politics was a waste of time, when the same resources could be used to take over the GOP from within. Republican voters, if not Republican elites, still wanted the party to be that of Nixon and Reagan, not just the Bushes — the party of the Rust Belt and Reagan Democrats, not just the party of Social Security privatizers and military contractors. Trump put the politics of Perot and Buchanan together into a winning force on the right and a winning force in the 2016 election. Whatever happens next year, this has changed American politics in a way that Perot’s symbolic achievement in 1992 never did. Yet if Perot had been more far-sighted in 2000, he might have hastened the populist realignment — and spared the country some of the hardships and disgraces of the last 20 years.

He was a self-made billionaire, a brilliant if eccentric businessman who could have been an equally significant figure in politics — if only he had been willing to treat populism as something more than the private possession of H. Ross Perot.