Baghdad

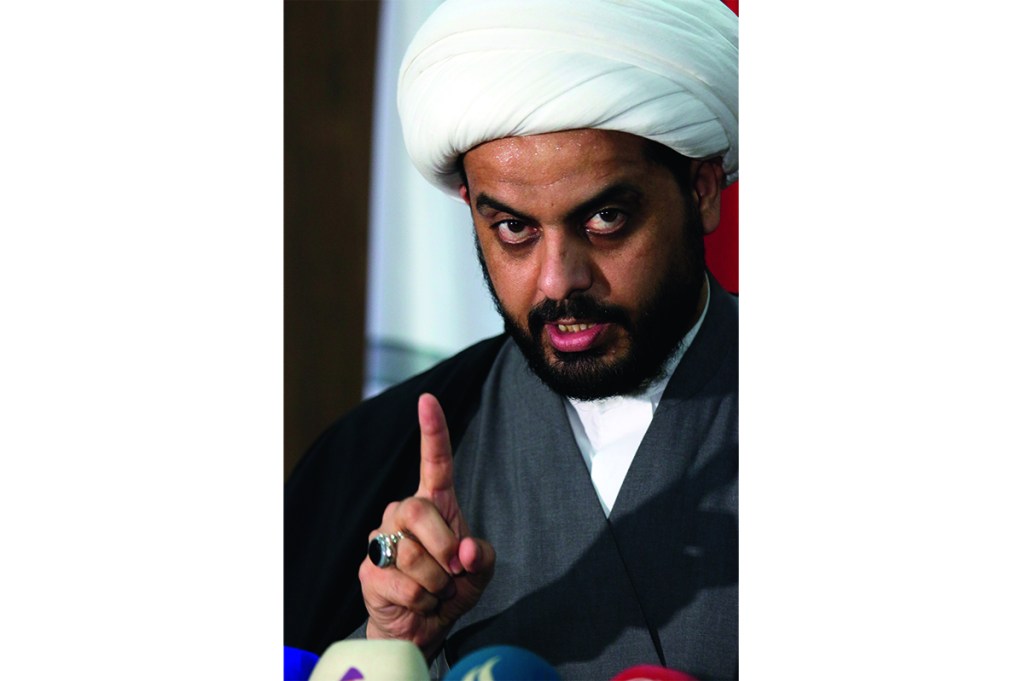

In the two months since the death of the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani, a number of local hard men have been vying to take his place. Most notable among them are his Iraqi sidekicks, the Gene and John Gotti of the Shia world: Qais al-Khazali and his brother Laith. Unless you’ve scanned Washington’s latest list of designated global terrorists, these two names won’t be familiar. Yet when I mention them in a Baghdad teahouse, people lower their voices and look around surreptitiously, as if discussing the Gotti boys in a Queens bar in the 1970s.

The Khazalis lead an extremist Shia group called the Asaib Ahl al-Haq, or League of the Righteous. Financed by Soleimani for nearly a decade and a half, the League is considered ruthless even by Iraqi militia standards. In October, its snipers were accused of shooting dead at least nine anti-government protesters in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, and it was put on an American blacklist. During the US occupation of Iraq, the League organized as many as 6,000 attacks on British and American forces, including a 2007 raid on a US base in which five soldiers were killed.

The League also ran prolific sectarian death squads, abducting, torturing and killing countless Sunni Iraqis. Such is the fear with which it is regarded that when it plastered 20,000 posters of Ayatollah Khamenei throughout Iraq a few years ago, city workers were too scared to remove them.

Since Soleimani’s assassination, Qais al-Khazali has been busy, shuttling off to Tehran for consultations and threatening to unleash his militiamen once more on American troops. A law only unto himself and his Persian paymasters, Qais is the kind of man Donald Trump is talking about when he says he wants to rid Iraq of militia control.

In which case, you might wonder, why didn’t Britain and America nab him when they were still in charge of the country, and he was killing our troops? In fact, they did. In 2007, two months after the murder of the five soldiers on the American base, Khazali was arrested in Basra by the SAS, Britain’s elite special forces unit. The problem was that three years later, as a result of one of the murkier episodes of the UK’s time in Iraq, Khazali was released to resume mayhem.

The coalition, you may recall, has form in releasing bad hombres back onto the streets. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the future Isis leader, was imprisoned at Camp Bucca before an American official deemed him fit for release. Unlike Baghdadi, however, Khazali didn’t get out by just quietly biding his time.

Instead, two months after the SAS grabbed him, Khazali’s followers staged an elaborate kidnapping operation, sending 100 men dressed as police to snatch five British men working at Baghdad’s finance ministry. Peter Moore, a British IT lecturer whose only crime was to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, was taken along with four bodyguards. Their captors sought to use them as bargaining chips for Qais al-Khazali.

One by one, the bodyguards were murdered. Moore, the sole survivor, was eventually released two years later, at the end of 2009. It was clear, though, that this was the result of a prisoner swap. A week later, Khazali was transferred from a coalition jail into the custody of the new Iraqi government, which released him immediately.

A prisoner swap is not how Britain chose to describe it at the time. Her Majesty’s government, after all, insists it never makes concessions to terrorist groups, let alone those who have already slaughtered hostages. The official line was that Khazali’s transfer to Iraqi custody was part of a program to cede judicial control back to Baghdad, which then chose to free him as part of an amnesty program for insurgency fighters. That it happened just days after Moore being freed was apparently a coincidence.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, few people bought that line — and Moore himself wasn’t one of them. He later told me that, in the final months of his captivity, Qais’s brother Laith visited to inform him that the prisoner swap would soon be going ahead. A British source very close to the negotiations explained to me that the exchange involved intensive lobbying of the American government, which had wanted Khazali to face proper justice for the murders of the five US soldiers.

True, if Britain had stuck rigidly to its ‘no concessions’ rule, Moore might never have come home. But the real scandal of this whole affair lies not in the moral flexibility of the British government, but in what happened after Khazali’s release by the Iraqis. Officially, this was conditional on the League laying down its arms and entering peaceful politics. Instead, it has embraced a ‘bullet and ballot’ strategy ever since, contesting elections while remaining fully armed, dangerous and loyal to Tehran.

Khazali holds court in Baghdad, giving interviews about the glory days of fighting the occupation, such as the time his followers shot down a British Lynx helicopter in 2006, killing five soldiers. His gunmen have also been in Syria helping Iran to defend Bashar al-Assad’s regime. More recently, the League has joined the fight against Isis in Mosul in northern Iraq — a worthy enough act in itself, but one which now gives the group the excuse it needs to keep its weapons.

Why has the League been allowed to get away with this? Partly, it’s because Iraq’s security forces are simply too weak to compel the Shia militias to disarm. The other reason, though, is that it suits Iran to keep such scary proxies on hand, as shown by October’s killings of demonstrators in Tahrir Square.

Not surprisingly, one of the protesters’ demands is an end to the militias like the League, whose offices in several Iraqi cities were attacked during the demonstrations. The protesters are part of a young generation sick of a political system where killing and kidnapping can get you what you want. In the case of Peter Moore and the bodyguards, it was Britain that was held to ransom. A decade later, it’s the whole of Iraq.

Colin Freeman is the author of The Curse of the Al Dulaimi Hotel: And Other Half-Truths from Baghdad (Monday Books). This article is in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition.