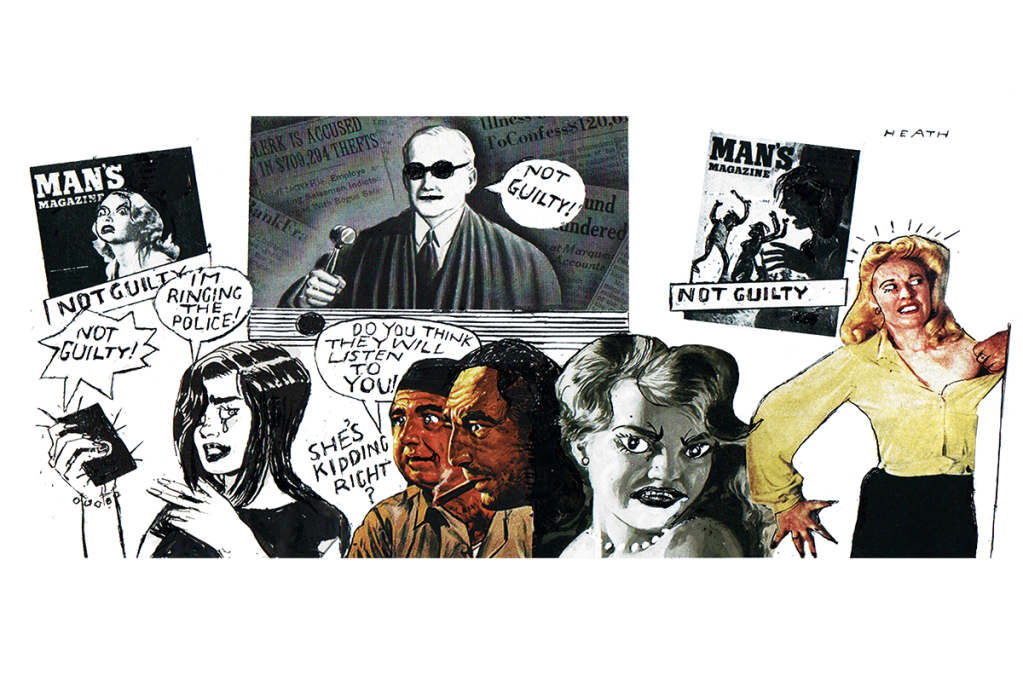

Five years have passed since Jodi Kantor, Megan Twohey and Ronan Farrow’s Pulitzer-winning reporting on sexual misconduct in Hollywood and beyond. Harvey Weinstein, #MeToo’s Perv Patient Zero, is in prison. Bill Cosby spent three years there as well. Woody Allen — Farrow’s estranged father, one-time accused child molester and husband of his ex-partner’s adult daughter — still walks free (not having actually been charged with anything), but a bunch of A-list actors won’t work with him, and you now have to preface every mention of Annie Hall with a handwringing disclaimer. Donald Trump, well, he wasn’t reelected, which has to count for something. The world, we were assured, would never be the same. Women were put in charge — and oglers (except for the handsome ones) were sent to the guillotine.

Or were they?

#MeToo, the movement against workplace sexual misconduct, changed everything and nothing. The “nothing” is in some ways easier to see: sexual harassment as a concern was not invented in 2017 (remember Anita Hill? or those 1990s television PSAs?), nor, in fact, was the expression MeToo, coined by Tarana Burke in 2006 in reference to sexual misconduct. The Obama administration took on sexual assault on college campuses in 2011. Feminists have been objecting to male sexual abuse since… the cave-feminists of premodern times.

The 2017 watershed budged, but didn’t exactly revolutionize, the legal status of sexual misconduct. The UK, for example, has since seen more sexual assault accusations but fewer convictions. It has not particularly improved the hopes of sexual harassment complainants in the United States. If anything has lessened the chances of a lewd boss lunging at a nubile employee, it’s the Covid-era rise of working from home.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Many of the initial hopes-slash-fears that men brought down by #MeToo would never show their faces in public again have proven unfounded. Louis C.K., fleetingly canceled for unsolicited masturbation, returned to the comedy scene fairly unscathed not long after. Jeffrey Toobin, another gentleman whose self-pleasure reached wider-than-optimal audiences, returned to CNN mere months after The Incident. (He has since departed, again.) Johnny Depp’s (partial) legal victory over his ex, Amber Heard — a thorny case of possible defamation, possible abuse and indisputably crummy behavior — suggested either that #BelieveWomen no longer mattered, or that it hadn’t ever mattered to begin with.

And as for a new order with women at the helm, Trump lost to Joe Biden, not any of the lady-Dem contenders. More recently, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, a development it’s difficult to interpret as evidence of feminist victory.

But #MeToo did change plenty on a cultural level. What began as an office (well, movie-set) anti-harassment campaign morphed into a broader rethinking of sexual norms. The new progressive approach involves taking not just formal relationships (boss-employee, etc.) but power dynamics into account when deciding whether a pairing is truly consensual. Any couple where one person makes a lot more money, or is more professionally accomplished, or has more Instagram followers — whatever — now elicits a concerned hmm.

Then there’s the matter of age gaps, or more specifically, the assumed problem of older men involved with younger women. Leonardo DiCaprio has never been #MeToo’d, and yet his apparent penchant for breaking up with girlfriends when they reach their mid-twenties has attracted enormous attention — he was roundly memed in August after breaking up with the model Camila Morrone after she turned twenty-five. Whole new categories of romantic partnership have become taboo, even when ostensibly between consenting adults: professors and former students, entertainers and fans. Age and status disparities started to be conflated with, in effect, sheer predation: even if both parties think they’re game, if there’s a difference in power, one must surely be prey.

This new way of looking at relationship dynamics has inspired a number of women to come up with revisionist histories of disappointing encounters. In some cases, women may indeed have been assaulted but didn’t have the language to convey it; one might credit #MeToo for providing that. In others, regret seems to have gotten rounded up to victimhood.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]#MeToo also marked an ideological reshuffling, with what was once called social liberalism joining classical liberalism among the liberalisms that are now understood as conservative. Where pre-#MeToo it was conservatives who insisted hook-up culture harmed young women, in the #MeToo years, this was reversed, and only contrarian sorts suggested women often enjoy casual sex and don’t necessarily find it traumatizing.

It’s hard to say how much #MeToo affected actual dating practices. Young and youngish people were already having less sex even in the years leading up to the Covid lockdowns. But the confluence of #MeToo and dating apps have made it socially unacceptable to hit on someone (particularly a female someone) in person. The idea is that apps make it possible to ask out only those who might be interested, while that hot barista might be monogamously partnered and not looking. Toss in the added awkwardness of a multiyear break from Real Life and who could tell what’s welcome or even acceptable? Are the times unsexy because #MeToo scared straight men straight, or have they simply decided other pursuits (porn, video games, arguing on the internet) are more fulfilling?

But the main contribution of #MeToo had less to do with anything specific to gender or sex, and far more with how society addresses wrongdoing in general. #MeToo formalized a new cultural template for dealing with bad behavior: cancel culture. Cancellation — a nebulous, disputed category — says less about specific crimes or consequences and more about an aura of Bad that hovers, forever, around certain individuals. A sort of wait isn’t he the one we’re not supposed to like anymore? persists even if charges are dropped, even if there were no charges and the original accusation is forgotten.

The “Shitty Media Men” list — a #MeToo-era document enumerating misdeeds substantiated and otherwise — inaugurated a certain type of activism. Its detractors call it witchhunting; its proponents see it as creating accountability. Accusations of “problematic” abound, situating those who’ve committed violent crimes next to that guy who was really rude that one time. It’s problematic if New York Review of Books editor Ian Buruma publishes a personal essay by disgraced Canadian media figure Jian Ghomeshi. It’s problematic if, like Matt Damon, you dare suggest that “there’s a spectrum of behavior” involved in sexual harassment — even if you stipulate it’s all unacceptable.

Without #MeToo, it would be impossible to make sense of the dynamics of the racial reckoning in summer 2020. Not the street protests, which are a fixture of social justice movements generally, but the endless cycles of accusation, apology and promises to do better in media and other white-collar professions. Much as #MeToo tried to solve sexism by identifying and shaming the sexists, the social justice movement that succeeded it sought to locate, and symbolically take down, the racists.

#MeToo was, in a roundabout way, a victim of its own success, as the framework it initiated was applied to women themselves. The racial awakening of summer 2020 saw the downfall of various white girlbosses, the shitty media women, as it were, who stood accused of racial rather than sexual misconduct. Overnight, Alison Roman went from vaunted New York Times food writer to go-to reference point for racial insensitivity, all for having criticized Marie Kondo and Chrissy Teigen in an interview.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]During Covid, “Karen” became the cultural personification of female anti-black racism: “Karen,” the demanding white woman, prepared to weaponize her white power or fragility or tears or whatever in order to get her way. It became untenable to think of women generally — rather a lot of whom are white — as a victimized caste. The idea that in all encounters between a man and a woman the man holds the power ceased to hold cultural sway. As this was the core assumption underlying #MeToo, its moment was clearly up. #BelieveWomen signs gave way to #BLM, and then the next thing.

And “women” as a category could no longer claim victimhood, once the vast majority — everyone who’s not transgender — were recast as cisgender women, a privileged category, in polite (progressive) society. When did that happen? Hard to pinpoint but certainly after #MeToo.

But mainly, as the mood among progressives shifted to calls to defund the police, #MeToo’s implicit tough-on-crime stance no longer fit. No one wanted to be a white feminist or a carceral feminist who called the cops if she thought a man — particularly a man of color — had looked at her funny. The urge to toss bad men in a cell and throw away the key may have remained, but what progressive would call for that now?

As an extrajudicial response to a failed system, #MeToo had no particular endgame for the men it tried to disappear. Were they meant never to work again, or just not to have high-profile jobs? Was the legal problem #MeToo addressed merely insufficient prosecution and conviction of existing sex crimes, or were new laws needed to crack down on the subtler forms of male misbehavior: ghosting after a hookup, for example, or requesting sex acts inspired by porn?

In the absence of an agreed-upon rehabilitation scheme, much discussion has hinged on dissecting the men’s public apology statements. Thus the many articles about whether comedian Aziz Ansari had properly atoned for having come on too strong on a date. Consider the Vox headline: “Aziz Ansari actually talked about the sexual misconduct allegation against him like an adult.” The subhed added, of course: “It wasn’t perfect.” Much discussion, then, of the quality of these apologies, but less of their intended recipients. Did Ansari’s victim — if “victim” is even the appropriate word here — deserve, or even want, an apology directed at Ansari’s comedy-show audience?

Every comeback felt too soon to movement proponents. But what was the appropriate length of time for a man to retreat from public eye before tentatively, apologetically, waving hello again? In a 2018 New Yorker article about various #MeToo’d men who had revived or attempted to revive their careers, Jia Tolentino wrote, “The laws of patriarchal physics dictate that for every act of sexual assault or harassment a man deserves an equal and opposite second chance.” Tolentino disapproved of that state of affairs, but what would be better? “It seemed to me essential, as a bare first step, for the man in question to understand that his experience is not inherently more important than the experiences of women, to acknowledge what he did, and that it was wrong.” If the aim of #MeToo was to get men to use proper language while expressing contrition, it was, as a sweeping societal reform, weak sauce.

Filling the void regarding what, practically, should be done about male misbehavior is a complicated neo-Victorianism. A number of temperamentally, if not always politically, conservative thinkers have stepped in to suggest that caddishness is a feature, not a bug, of sexual liberation. Rather than inventing ever more complicated definitions of consent, they suggest the entire system of casual sex needs burning down.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Recent books such as Christine Emba’s Rethinking Sex and Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution argue for a return to sexual conservatism. Katherine Dee guested on the Savage Lovecast and lectured Dan Savage’s listeners about sex negativity. A nostalgic, traditionalist mood pervades the culture, with writers such as Helen Andrews questioning whether women should be putting their careers first. If #MeToo was about making the workplace safe for women, the post-#MeToo moment has included takes that would keep women out of the workforce.

Early on #MeToo was criticized for infantilizing women by assuming their lack of agency, for curtailing their freedom to act as they chose. But at least it made women safer, right? If not, what, exactly, was the point?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.