‘How have you been?’ David Cameron asks, bounding up to meet me. Fine, I say, then make the mistake of asking him the same question. His face drops. ‘Oh,’ he says. ‘Well. So-so.’ Watching the political news, he says, has been getting him down (in a way it didn’t when he was in office) and if you’ve picked up a British newspaper in recent days, you’ll know why. His memoir, For the Record, is out and the extracts make it sound like a 700-page apology note to the nation. He’s sorry for the referendum result. Sorry for what came after. And above all, sorry for letting villains like Boris Johnson and Michael Gove get away with it.

Standing in his jogging kit, fresh from his morning run, the former prime minister still looks a bit deflated. His Big Sorry, he says, is a prerequisite for being heard on anything else. ‘In my position, you can’t really complain and say: forget about the referendum and read the rest of the book,’ he says. ‘I do want to win domestic arguments. But I can’t do that unless I address the elephant in the room, which is what has happened since the referendum.’ An almighty mess, and one which he admits to having had a pretty big part in creating.

We meet in his new office, which bears a striking resemblance to his old one: a Georgian townhouse with an imposing black door and a grand stairwell. The logo on the T-shirt he’s wearing looks like a pastiche of a Soviet flag, which reminds me of one of our first Spectator covers about him: ‘Is Cameron a revolutionary?’ we asked. The answer turned out to be yes. Lower taxes and welfare reform led to the greatest jobs boom in history. Inequality fell to its lowest for a generation. School reform meant the best state schools now outperform the best private schools. Plenty to boast about — if he were in the mood for boasting.

‘Every time I wrote a chapter, I asked myself: which decisions went well, and which decisions went badly?’ he says. ‘I’m sure there are mistakes I haven’t owned up to. But I tried to ask these questions of myself, because I think that’s what you owe to people.’ The frankness is there from the start. He writes that at Eton he was a mediocre student prone to mixing with the wrong crowd. He confesses that he smoked marijuana, and narrowly escaped being expelled. He has dodged questions about drug use in later life, he says, because he was guilty: he did have the odd spliff with his wife’s friends. But the book is suspiciously silent on whether he took harder drugs: I ask why. ‘I think I’ve said all I want to say,’ he says. One for the sequel, then.

There’s a fair chunk about his time as opposition leader, leading the party into what he (then) regarded as modernity. It worked, but not well enough to win a majority. On austerity, his regret is ‘that we probably didn’t cut enough’.

‘It’s easy to say this with hindsight,’ he says. ‘I mean, I didn’t particularly feel that at the time. But looking back, if I was advising someone in the same situation again I’d say: don’t make cheeseparing cuts.’ The Tories cut slowly, over years: Ireland and Iceland, he says, cut deeper — and recovered pretty fast.

Things start to go wrong in his story during the Scottish referendum of 2014. Not that he seems to notice. That chapter is oddly triumphant. The separatist vote surged, and the union almost ended: the result was 55/45. But it’s written up as a clear victory. (‘Our union was safe. The argument is over.’) At the time, the campaign he led was dubbed Project Fear and seen by many Scots as a case study in how to almost lose a referendum. I ask why he sees it so differently: was the argument really over? ‘It felt like that then,’ he says.

I ask if it might have served as a warning: the Scottish National party’s emotional argument (about nationhood, belonging and sovereignty) working better than Project Fear warnings. ‘I don’t accept that,’ he says. ‘I did make the argument about the EU’s contribution to peace on the continent. But it didn’t break through. It was kind of “Cameron predicts World War 3”. It didn’t have the impact.’

His recollections of his time in Europe show him doing his best to reform, but being outmaneuvered every time — especially on having Jean-Claude Juncker as president of the EU Commission. ‘Many national leaders told me privately that they opposed Juncker’s appointment, including Angela Merkel,’ he recalls. He couldn’t work it out: given that the appointment was up to them, couldn’t they do something about him? He records how he stayed up drinking wine with them until 2 a.m. discussing how to stop it. (‘I was tired, but I didn’t dare leave in case they cooked something up without me.’) But when Merkel went wobbly (her mother, she told a baffled Cameron, wanted Juncker), the others backed down. He talks about ‘Angela Merkel’s half-life’: the length of time it took between her making a promise and then breaking it. The reader is left thinking: isn’t it clear what’s going to happen next? They won’t give you the renegotiation you want! It’s a trap!

But that’s not how he saw it then — or now. He still regards his renegotiation of EU membership as the best deal anyone could have secured. ‘For the French to suddenly stop saying the euro is the currency of the European Union, that the pound is also a currency of the European Union: I mean, that was massive.’ But he accepts it didn’t seem so to those whose expectations had been raised by his earlier statements.

He started telling his cabinet colleagues that the renegotiation was the start of a process, the sign of more to come. ‘I used to say to Boris: look, we achieved a certain amount through this renegotiation. At some stage there will be another treaty negotiation. You might well be the prime minister going into that treaty negotiation. There are other things you’ll be able to change.’ But Johnson and Gove concluded that the EU was never going to reform and decided to back Brexit.

In the book, their decision is portrayed as cynical. Suddenly his ‘complete soulmate’ — Gove — was his enemy. ‘He had been such a key member of my team. He’d said he wasn’t going to play any part in the campaign, because he said he was so uncertain about it.’ But was this really a betrayal? Might it be that both men just decided they wanted Britain to leave the EU? ‘I can just tell you what I felt,’ he says. ‘If you’re writing a book, for the record, you should say what you did and didn’t expect. I don’t think he ever envisaged himself standing in front of a poster of Turkey saying that 80 million Turks were going to come into Britain.’

A bit of an exaggeration, but we are now in the Brexit twilight zone where every-thing is hyped up, and one man’s point of principle is another’s betrayal. I ask why the harshest language in the book (which is pretty nice about most people) is reserved for Gove. ‘Well, that came off the tape,’ he says.

Which takes us to an interesting point about how the Cameron memoirs were written. Throughout his premiership, he would unburden himself to Daniel Finkelstein of the Times (whom he ennobled six years ago). Their monthly conversations were recorded, and the transcript used as notes for these memoirs. He would send each chapter to Lord Finkelstein, who would send it back suggesting improvements. ‘I used to tease him. I said: I’ve sent you a 5,000-word chapter and you’ve sent me back a 5,500-word chapter. Editors are meant to cut these things!’ The result is a memoir that is part retrospective, part-diary.

I mention a scene he did not include: February 2016, when his renegotiation was going badly and he found himself at a birthday party for Frances Osborne, the wife of the (then) chancellor. Andrew Roberts, the historian, took him aside and said that if he wished to be a great prime minister, it was clear what he should do: reject the EU’s offer, campaign for Leave, win 60-40, then change politics for ever. I ask if he wishes that he’d taken this advice, and he pauses. ‘I didn’t think it was the right answer.’

Reading the book, it’s still not entirely clear why. Full-blooded Euroskepticism runs through its pages from the get-go. It could be a manifesto for Leave until about Chapter 40. But at the end, the question of Europe suddenly morphs into a battle between the forces of light and darkness.

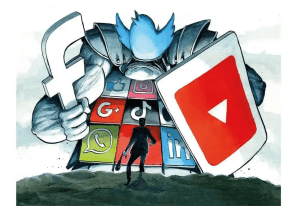

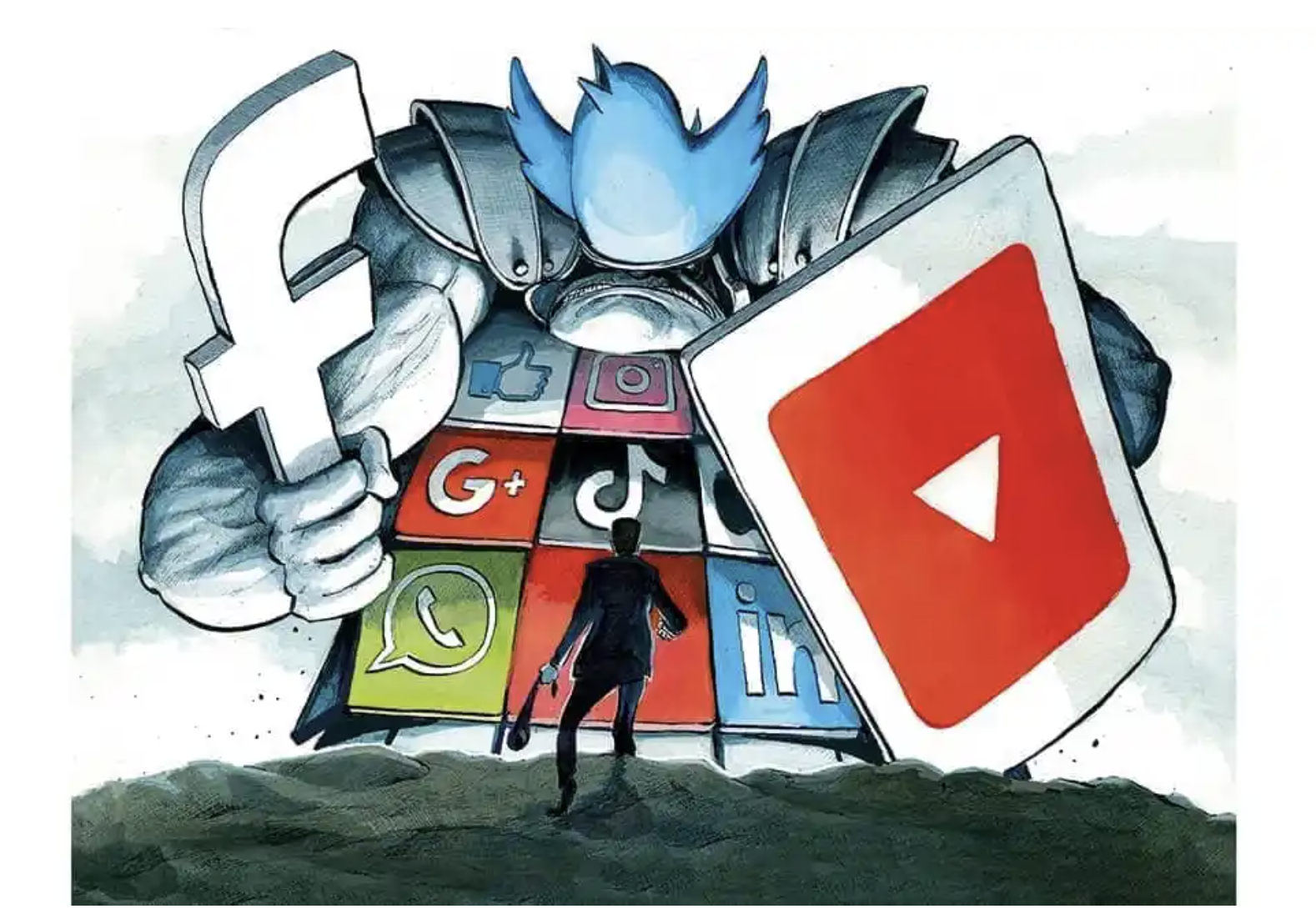

He describes it in one of the book’s most striking passages. ‘Every trait of the age of populism — the prominence of social media, the emergence of fake news, anti-establishment sentiment, growing unease with globalization … appeared to conspire against our cause. It wasn’t that Leave was besting us in every battle. It was that the physics of politics seemed to have changed. The upper hand became the losing hand, and the higher ground — which we felt we had captured — was surrounded.’

There is another explanation: that modernity ended up taking a different form to that which Tory modernizers were expecting. Voters felt globalism had overreached and sought to dial it back. And the referendum presented people with the perfect opportunity to express this. Fredrik Reinfeldt, his Swedish counterpart, once told me that prime ministers are distracted by government, so they can miss new political trends and concerns.

I ask Cameron if, looking back, that was true for him. No, he says, he always knew he was ‘trying to govern in the age of populism’. This is why he was against tax cuts for the richest, and tough on Brussels: he says he always felt the public concern. ‘That’s why we were so passionate about trying to get immigration under greater control. Lots of people, you included, were upset by that.’ High minimum wages raised the incomes of the poorest the most. ‘People were worried about economic insecurity. Worried about culture and security, with immigration too high. And they said: “By the way, this thing called Europe had eight members when we last voted. It’s now got 28. When are you going to ask us about it?” I was trying to address these things.’

This, it seems, is the worst aspect of it for him. He saw all of this coming, and tried to respond, but failed, in a way that would eclipse all else. ‘That’s why the “I’m sorry, I failed” line is so important. Because in the end, the solution I sought did not come through.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.