When the last Tory government fell, the famous question after election night was: “Were you up for Portillo?” Were you awake in the small hours when the man many expected to be the next leader lost his seat?

This year, there’s no shortage of big beasts likely to be turfed out by the electorate. Jeremy Hunt, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Grant Shapps are just some of those tipped to lose their seats. Many touted as potential leaders — Penny Mordaunt, Miriam Cates and James Cleverly — are also endangered. If current polls are to be believed, the Tories could be reduced to a rump of about 100 members of parliament and Keir Starmer will be sitting with one of the largest majorities in parliamentary history.

Tories fear that the BBC and other broadcasters will treat them as a fringe party

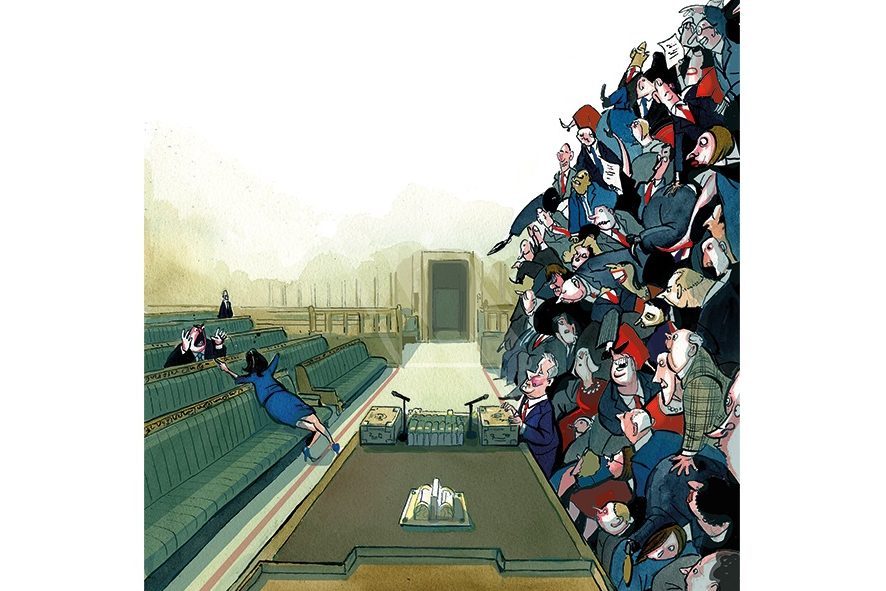

The word “landslide” doesn’t quite capture the scale of it. Tony Blair had a majority of 179 members in 1997, the biggest since 1931. According to a recent Survation MRP poll, Starmer is on course for a 286-seat majority, which would mean his members occupy about three quarters of the Commons. The 100-odd Tories and sixty-odd Liberal Democrats and SNP members will be there to ask questions, but they’re unlikely to present much of a serious threat to Starmer. The more important opposition would be likely to come from his own ranks. Starmer would be managing one of the biggest cohorts of backbenchers any prime minister has had to deal with: about 300 in all.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Tory members are beginning to believe that this horror show is possible. Comparisons are being made with the 1993 Canadian general election, in which the Conservatives lost 154 of their 156 MPs. Tories fear that the BBC and other broadcasters will treat them as a fringe party.

In this scenario the Labour Party would in effect be both the government and the opposition. The nature of not just government but politics would be changed. All the important tensions in policymaking — from economics to net zero to Israel/Palestine — would be between Labour factions. Ideas seen to be daring now — pushing through planning reform or even state regulation of the press — could be law in a heartbeat and a large flock of younger members would be more open to modernization.

The Westminster ecosystem would also change, with think tanks — from UCL’s Policy Lab to the Resolution Foundation to Morgan McSweeney’s old outfit Labour Together to the Tony Blair Institute (or what will be left of it after the expected mass transfer of staff to the Labour ranks) — competing for influence. Blair has already established himself in a stately home near Chequers.

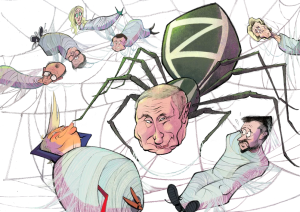

Right now the Tories exert a gravitational pull on Starmer. A YouGov poll shows that about half of those who voted Tory in 2019 will not do so this time — and Starmer is keen to win those voters over. He has even saluted Margaret Thatcher’s boldness. Rachel Reeves emphasizes fiscal discipline and talks as if (while not quite promising) she won’t splurge or raise personal taxes.

Once in power, this dynamic will change. An emboldened Labour Party will face a rare moment of genuine power and potentially a majority bigger than that of Thatcher, Blair or even Attlee. It’s not hard to imagine Labour backbenchers urging a cautious Starmer to seize the moment and push for radical reform while he still can. “You are only going to get one chance to make bold, structural changes. Look at Blair’s second term,” says one party figure, pointing to how 9/11 then changed everything.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Starmer’s people are not keen to talk about the implications of a mega-landslide. They fear that looking complacent might be off-putting to voters. “Not one vote has been cast” says a senior figure. This week marked the anniversary of the 1992 Sheffield Rally, where Neil Kinnock’s triumphalism was seen to have dismayed voters and turned Labour’s lead into an unexpected defeat. Starmer’s team say that the polls will narrow, and point out that they need to win 120 seats from the Tories to have a majority of just one.

‘You would start off with hedonistic euphoria. Then people would move to start indulging themselves’

A super-majority would also bring problems of its own. As a former whip puts it: “You would start off with hedonistic euphoria. Things would calm down and then people would move to start indulging themselves. That’s when you would have problems.”

When Starmer first became Labour leader, his aides spent much time thinking about the “Squad” in Washington — the four Democrat congresswomen, led by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who became an internal opposition as they tried to push their party to the left. It’s one of the reasons why selecting “Starmtroopers” who could be relied on to be team players has been crucial. But many of them are new to politics, not just Westminster. There has been an effort to recruit candidates from a range of professions — from ex-military to vaccine scientists — rather than from just within the party. About half of Labour members will have no experience of parliament — no postwar party would have experienced a change like it.

Mindful of the experience of the Red Wall Tories after 2019 — many of whom were astonished to be elected — Labour is trying to train candidates in what is effectively a Westminster finishing school. The aim is to build the parliamentary party equivalent of a “Ferrari.” The training ranges from how parliament works to campaigning, public speaking and even posture. There’s also a sense that they need to get the balance right between constituency and parliament. New Labour grandees say that one of their mistakes in 1997 was to be too heavy-handed about the dangers of Westminster, which meant the new members spent too much time in their constituencies.

Some of the training sessions are in person, with actual away days, even overnight sessions. The most regular sessions though are online, almost weekly, and held with Starmer’s top team, including Morgan McSweeney and Pat McFadden, now Starmer’s right-hand men. They go through campaign messaging and set monthly campaign targets for candidates to meet.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Shadow ministers also sometimes make an appearance. Last month, deputy-prime-minister-in-waiting Angela Rayner appeared on the call to give a rallying cry about how candidates need to stay focused and fight on after Rishi Sunak had “bottled it” on a May election. “They are often pep talks,” says one attendee.

A test of loyalty came when Starmer ditched his key election pledge to spend $35 billion a year on Green issues. Rachel Reeves and Ed Miliband gave candidates a joint briefing call on the U-turn. One might have expected complaints but rather than anger at being marched up and down a Green hill, the session was dominated by candidates thanking them both — and asking if there would be a briefing paper of lines to take, so that they stayed on-message.

But though the party is well-behaved, there’s a question over how long that will last once it is in power. “We all want to win. But once the shadow cabinet are in departments with teams, there will be some muscle-flexing I’m sure,” says a Labour aide.

Blair used his mega-majority in the first term to focus on constitutional change — devolution, the new supreme court and quangos — to reshape the political landscape in a way more favorable to Labour. Starmer can quickly do some things — votes for sixteen-year-olds and EU citizens — to reform the landscape even more to his advantage.

At one stage, the Tories worried that he’d team up with the Liberal Democrats to change the voting system, but they have no fear of that now. The old Westminster system, designed to turn close elections into big majorities, could be about to give Starmer more power than any leader in Europe.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazines. Subscribe to the World edition here.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]

Leave a Reply