In the Tennessee House of Representatives, it went by the name of Bill 9; in the Tennessee Senate, Bill 3. And the Volunteer State’s governor, whose first name is also Bill — that would be Republican Bill Lee, in office since 2019 — signed it last Friday. The new law makes it illegal for “male or female impersonators” to “provide entertainment that appeals to a prurient interest” in a location where minors might be present. A first violation would be a misdemeanor; a second, a felony.

The law, as you may already be aware, comes in response to a bizarre and unpalatable recent development known as Drag Queen Story Hour. The phenomenon is the brainchild of lesbian activist Michelle Tea, a former sex worker and author of several books, including the memoir Rent Girl; something called Modern Tarot: Connecting with Your Higher Self through the Wisdom of the Cards; Astro Baby, “[o]ne of the first-ever books about astrology for kids”; and, most apposite of all, Tabitha and Magoo Dress Up Too, a children’s story about a cross-dressing boy and girl who learn from a drag queen how “to defy restrictive gender roles and celebrate being themselves.”

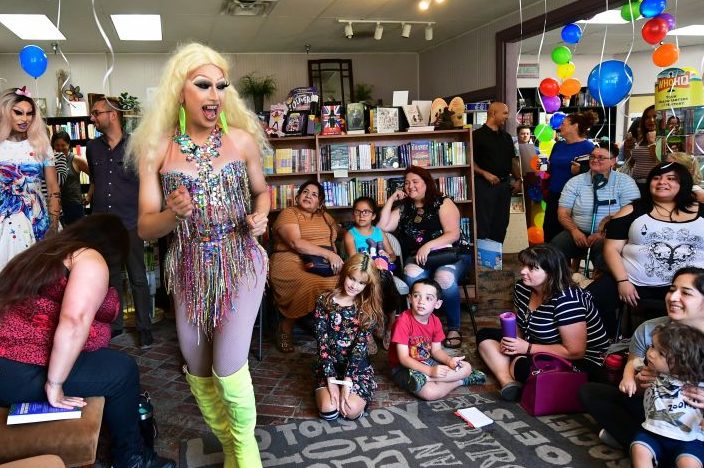

That self-celebration, as it happens, takes place at a Drag Queen Story Hour (DQSH). Founded by Tea in San Francisco in 2015, DQSH has, like Covid-19 and K-Pop, spread around the world. Its dozens of official US chapters sponsor readings at schools, bookstores, libraries, and other venues, and in many cases receive ample taxpayer funding. The storytellers are men in full drag get-up; the audiences are small tots and their parents. Some of the readings are from ordinary children’s stories, including classics; others are works — which, these days, roll off the presses with surprising frequency — explicitly designed to introduce youngsters to cross-dressing and gender identity.

Take Julián is a Mermaid (2018). It’s about a boy of six or seven who, espying drag queens in mermaid garb on the subway, decides he’s a mermaid, too; at story’s end, he’s taken by his supportive granny to a drag parade. The book’s author, Jessica Love, has stated publicly that we’re meant to recognize Julián as transgender. This is the message of many of these books: that tykes who might just enjoy playing dress-up — or who might turn out to be gay — are, in fact, candidates for “gender-affirmative” treatments. There’s no way of knowing how many kids’ attendance at a DQSH event has been the first step on their way to puberty blockers, hormone injections, and surgical mutilation.

I’ve seen more than my share of drag shows — never intentionally. I’ll be relaxing innocently with a drink at some gay bar when suddenly there’s a loud, brash guy in a gown strutting from table to table, insulting the customers, usually in exceedingly vulgar fashion, and/or violating other men’s personal space in ways that would lead many a woman to call the cops. It’s invariably unpleasant, and rarely amusing. Frankly, the whole schtick seems often to be an excuse for a gay man to vent his anger — especially at better-adjusted gay men and women generally.

To be sure, I assume most of the performers involved in DQSH aren’t doing blue material or getting handsy with the moppets (although there have been disturbing anecdotes to the contrary). Still, why the sudden eagerness of left-wing establishment types to treat these practitioners of a quintessentially silly activity as if they were all Martin Luther King, Jr.? Why are so many parents desperate for their offspring to be read to by grown men in dresses? Why, to turn it around, would an emotionally mature adult male want to slap on a frock and read to other people’s progeny? And why do teachers, librarians, and other professionals consider it so important to make this happen?

For what it’s worth, I suspect that most of the folks promoting these events are misguided progressives who think they’re helping to train tender minds to look kindly upon what they perceive as a beleaguered minority. But more than a few, as their rhetoric makes clear, are revolutionary postmodern zealots — contemptuous of capitalism and steeped in that intellectual abomination known as queer theory — for whom DQSH is a splendid means of exploiting the inability of little lads and lassies to distinguish fact from fantasy. The kids are thereby lured into a tantalizing and imaginative world in which such real-world bourgeois phenomena as sexual boundaries, family ties, and the very concept of childhood innocence can be undermined, while transgenderism, prostitution, and even pedophilia are normalized, and the darlings, with any luck, are brainwashed into believing they were born in the wrong body. (Like Michelle Tea, with her kiddie books on astrology and drag, such activists know that it’s best to get to them while they’re young and clueless.)

As for the drag queens, most of them may well be harmless enough, grasping, as ever, at an opportunity for unearned attention. But there’s no escaping the fact that there’s always at least something of a sexual element to drag — and that several DQSH participants have (surprise!) turned out to be registered child molesters.

The motive for the Tennessee law, then, is understandable. Yet I fear it’s more than a bit too broadly written. Would it prohibit pre-teens from seeing, say, the Australian comedian Barry Humphries cavort onstage as Dame Edna Everage, one of the most hilarious characters of all time? Would a third-grade class be allowed to attend a performance of Peter Pan in which the title role was (in accordance with long tradition) played by a woman? Would a boy in a school talent show be allowed to put on a dress to reprise something like Dan Aykroyd’s gut-busting 1978 Julia Child sketch from Saturday Night Live? Come to think of it, does Tony Curtis’s performance in Some Like It Hot count as appealing to a “prurient interest”? I know Marlene Dietrich’s iconic tuxedo turn in Morocco does. And I’m glad I saw both movies in my boyhood.

Yes, I’m all for protecting kids from creeps. But in this case I think the legislators in Nashville could have written a better law.