Eight law enforcement officials, including three policemen and five members of a local anti-jihadist force, were killed in a jihadist attack in Burkina Faso on Tuesday. Jihadist raids on two military bases in Somalia, using suicide car bombers, killed 23 on Saturday. On Friday, South Africa decided to deploy its troops in bordering Mozambique, days after Islamist militants took over the town of Palma, killing dozens of locals and forcing thousands to flee.

The past week is only a sample of the jihadist peril currently engulfing Africa. These terror attacks reaffirm the growing strength of the world’s deadliest jihadist groups, including al-Shabaab, Isis, al-Qaeda, Boko Haram and their affiliates. The global ramifications of the snowballing jihadist insurgency in the continent can be gauged by French energy firm Total withdrawing its staff from Mozambique; the thwarting of UNICEF and the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 vaccination efforts in Somalia; or the Joe Biden regime reaffirming its presence in Burkina Faso and other Sahel states to ‘prevent attacks on US soil’.

In recent years we have witnessed the birth and rise of an African Islamic State, a multi-pronged jihadist umbrella organization originating near the Lake Chad Basin, gradually spreading through Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon. In February 2020, a meeting of jihadist groups led by al-Qaeda was held in Mali, featuring Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (Support Group for Islam and Muslims) and the Macina Liberation Front, to underline al-Qaeda’s plans to spread toward the Gulf of Guinea. On cue, jihadist raids have escalated in the Ivory Coast, with Islamist militants also launching attacks in Benin, Togo and Ghana. Al-Shabaab in Somalia is also allied with al-Qaeda, while Boko Harm’s surge in West Africa is also working in tandem with jihadist groups such as Isis.

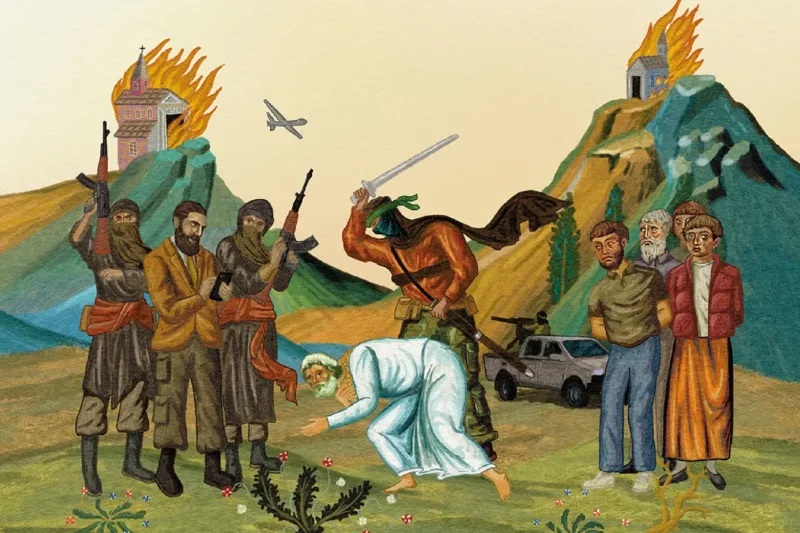

Isis, similarly, is using its allies across the continent to spread terror. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) which is linked to Isis massacred 23 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) last week. Isis has also continued its jihadist maneuvers in North Africa, especially Tunisia and Libya — the two African countries which contributed the most fighters, and even overseas territory, to the original Isis ‘caliphate’ in Iraq and Syria. Since Isis’s shift of focus to Africa the jihadist group has unleashed some of its goriest violence in Mozambique, beheading children, torching homes, turning soccer fields into execution grounds, and in turn displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

The radical Salafi brand of Islam common to Isis, al-Qaeda, Boko Haram and al-Shabaab is rooted in the puritanical Islamist movements originating in the 19th century Middle East. In addition to hardline resistance to ideas and values they deem ‘Western’ or ‘European’ their version of Islam is similarly dismissive of contrasting Islamic teachings of other sects, denouncing them as ‘heresy’. And just as in the Middle East and South Asia, Salafi jihadist outfits have targeted the pluralistic core of Africa. Therefore, just as needed as global peacekeeping missions, military training and capacity building measures are efforts to counter the ideological lure of these jihadist groups.

Like in other parts of the world, a vast majority of mainstream Muslim organizations officially reject Isis and other global jihadist groups. But many of these organizations have struggled to denounce the violent beliefs espoused by jihadists. Indeed, many of these beliefs which suppress fundamental human rights are now law in many Muslim states.

When the Islamic State first emerged in Iraq and Levant, it was pointed out that many of its fundamental beliefs were similar to that of Saudi Arabia — the chief propagator of Salafism around the Muslim world — where ‘crimes’ such as sorcery, homosexuality, apostasy and blasphemy are still punishable by death. The excommunication, and elimination, of pluralistic Islamic sects and ideas, known as takfir, forms the foundation of jihadism, with Muslims being the primary victims of Islamist terror outfits in the Muslim world.

Religious minorities are specific targets in these countries. Jihadist violence against Christians is on the rise in Africa, with over 11,500 Christians killed in Nigeria alone over the past six years. In Christian-majority Mozambique and DRC, churches continue to be targeted with increasing frequency in anti-Christian jihadist violence.

In addition to delegitimizing the jihadist groups through counter-narratives, it is critical that local authorities fill the governance vacuum that allows these outfits to flourish. Failure to address the East African famine facilitated al-Shabaab’s recruitment at the start of the previous decade. Governance failures in Nigerian state of Borno allowed Boko Haram to step in and take charge. The south-westward surge of al-Qaeda and its affiliates in West Africa is facilitated by political crises marring the states in the region.

A multifaceted, globally coordinated, effort is needed to curb the jihadist surge in Africa. The swathes of power vacuum and governance crises in the continent dwarf South Asia and the Middle East, pinning local populations against a precipitously rising genocidal threat. If these voids continue to be filled by radical Islamist militia, and the growing jihadist network, an unprecedented threat could await the rest of the world.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.