Democracy is dying in Thailand — or perhaps it’s already dead. Thailand’s constitutional court this week ordered the dissolution of the country’s most dynamic and popular political party. This ruling is a decisive blow to an already wounded Thai democracy.

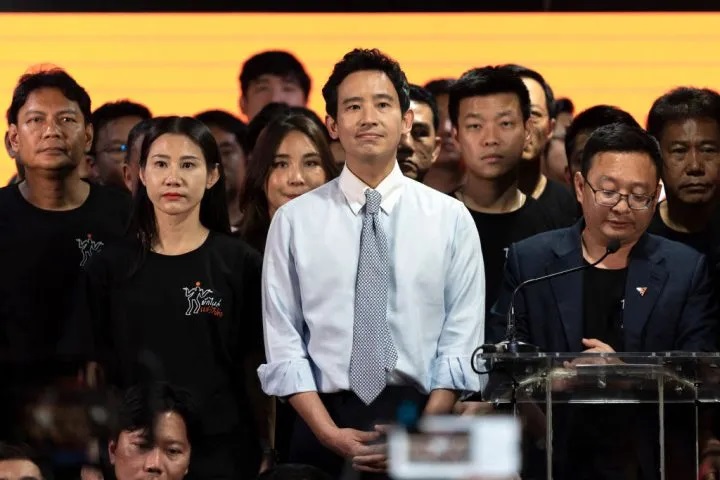

The Move Forward Party’s (MFP) “crime,” according to the court, was to call for the country’s strict “lèse-majesté” laws to be reformed. The judges imposed ten-year political bans on all of its leading party members, including former leader Pita Limjaroenrat.

Thailand has always been able to present the illusion that it is a democratic country

Human rights groups and huge swathes of the voting population view the allegations as politically motivated and unfounded in evidence. So why did the nine judges make this deliberation?

The case mostly boils down to protecting the royal family from any form of criticism. In Thailand, scrutiny of the royal palace is deeply taboo. Speaking out against it can be legally tenuous, in some cases physically dangerous. Since 2020, at least 303 people have been charged under royal defamation laws; many have ended up in prison for social media posts, attending protests or giving speeches that were perceived as critical of the monarchy. Over 1,000 others are facing political charges related to rallies over the last three years.

But the court’s decision on Wednesday is also about ensuring that Thailand’s conservative-royalist elite remain in power. They were motivated by a desire to guarantee that no single person, community, or political party can threaten Thai conservative elite hegemony. The status quo must not be questioned. And if it is, whoever is questioning it may face up to fifteen years in prison per charge.

The MFP was without a doubt the most vocal group in Thai history when it came to openly discussing the monarchy. But they also called for other Thai laws to be changed too. Its members, namely Pita Limjaroenrat, hoped to toss out the country’s forced military conscription laws which force thousands of young men into the military every year.

They also demanded equal rights for members of the LGBTI+ community, promising to amend legislation. The MFP openly pointed out rampant systemic corruption and promised to establish policies that would safeguard human rights and protect refugees fleeing war in neighboring Myanmar. All in all, this potential change appears to have been too much for the ruling establishment.

In Thailand’s 2023 general election, the MFP performed remarkably well, emerging as the party with the most seats in the House of Representatives. They won 151 out of 500 seats, signaling a significant shift in Thai politics as the party captured the support of many young voters, reflecting a widespread desire for political reform. But Pita did not become prime minister.

Despite winning the most seats in the House, the MFP lacked support from the military-appointed Senate, which sided with conservative and establishment interests. Pita also faced legal challenges regarding his ownership of media shares, raising more questions from the election commission about his eligibility.

When it was announced that Pita wouldn’t become PM, it dawned on the majority of voters that their vote had counted for nothing. They had cast their ballots for Pita, but instead got Srettha Thavisin, a candidate from a rival opposition party that is seen as outdated. On top of this, Srettha is widely viewed by critics as a puppet for the Thai establishment.

What makes the court’s ruling even more heartbreaking for the country is that this isn’t the first time this has happened. In February 2020, Thailand’s constitutional court ordered the dissolution of the Future Forward Party (FFP), a progressive political party and the MFP’s predecessor which had gained significant popularity since its establishment in 2018. The court ruled that the party had violated electoral laws too. The decision was met with widespread criticism and protests, as many viewed it as politically motivated.

Despite a lingering global perception that Thailand is a beacon of equality and liberty in Southeast Asia, the truth is that democracy has always struggled to stick in the Kingdom. Although the courts are now the elites’ go-to course for silencing dissent, in the preceding decades, military coup d’états were the tool of choice for maintaining power by force.

Thailand has experienced a total of thirteen successful military coups since it became a constitutional monarchy in 1932. These coups have frequently interrupted civilian rule, created ongoing political instability and revealed the military’s significant influence in the country’s governance. For almost a decade, the country was led by Prayut Chan o-Cha, a military dictator. Seizing power in a 2014 coup, he continued to rule the country until 2023 through what many say was a rigged or at least questionable election in 2019.

Under the authoritarian state of Prayut, dozens of political activists fled the country as authorities rounded up political dissidents and harrased critics. Since 2016, at least nine Thai activists, some of them critics of the monarchy, have either gone missing or been found dead under mysterious circumstances.

The latest disappearance — that of Wanchalearm Satsaksit in 2020 — galvanized a massive protest movement that called for democratic principles, wider civil liberties, and finally, a curbing of the monarchy’s massive powers. But it was this last call that resulted in a sweeping violent crackdown on the mostly Millenial and Gen Z protesters.

Yet unlike its authoritarian neighbors Cambodia and Myanmar, Thailand has always been able to present the illusion that it is a democratic country to foreign investors and most importantly to its millions of tourists each year. It’s unclear what is next for the country, but what is certain is that the illusion of democracy is quickly disappearing.

When speaking to Thais who voted for MFP, some say this could be a catalyst for new demonstrations. Others, however, feel demoralised, knowing that the last round of protests ended in violence and huge waves of legal charges.

Ultimately, after this week’s decision, it is impossible to perceive Thailand as a democracy. At best it is a quasi-democracy of some form, an autocratic political system where the military and royalist establishment still remain at the top. Today, Thai citizens are waking up to the familiar sense that democracy in Thailand is fragile, and for now at least — out of reach.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply