Cast your mind back to the 1990s for a moment. The left, dispirited at their generation-long rout at the hands of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, and enraged by the ratification of limited-government trends at the hands of Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, were looking for a new rallying point. By the end of the decade, the intellectual left had settled upon a new epithet: “neoliberalism.”

Although the term was not brand new, it exploded in popularity in left academic journals and soon in left media too. Simply put, “neoliberalism” means “democratic capitalism.” Even more simply, it is a label for anything and everything the left doesn’t like (it has become fully intertwined with that other all-purpose epithet, “racism”), a new bottle for old wine, a back door to revive that old-timey socialist religion.

Anyone not a leftist might think there isn’t much to see here. Except that over the last couple of years, the term has started showing up on the right, with much the same definition and critical connotation as the left. These days, the use of “neoliberalism” as an epithet can be found in such staid, established conservative journals as National Review and in right-wing populist online outlets such as American Greatness and the American Conservative. This odd rhetorical convergence points to a larger development within conservatism that is still not fully recognized — the expulsion of libertarianism and neoconservatism from the conservative movement by the newest thing to hit the political scene: “national conservatism.”

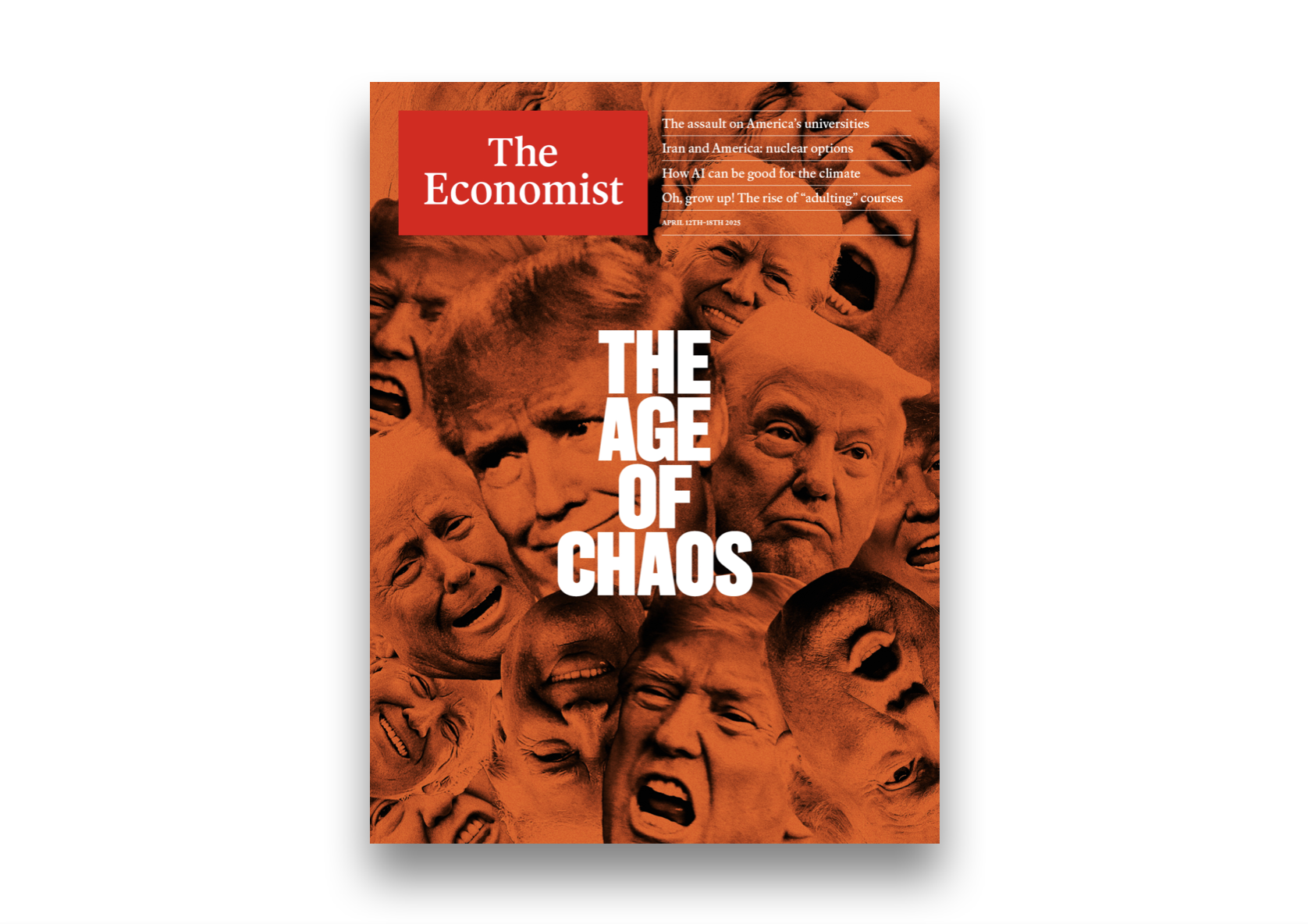

It is not immediately obvious that a rejection of libertarianism and neoconservatism is the irreducible common denominator of the self-consciously styled “national conservatism” movement, which sprang up on both sides of the Atlantic coincident with Brexit and the surprise election of Donald Trump. The deeper reason behind this twin rejection reveals the essence of a national conservatism that otherwise seems fractious, contradictory, sometimes incoherent and (therefore) unstable.

Libertarianism and neoconservatism would seem to have little in common, when not directly opposed. Yet their expulsion from the conservative coalition would have seemed unthinkable as recently as a decade ago. The modern American conservative movement, both intellectually and politically, was defined for decades as a three-legged stool. Those legs were “economic conservatives,” who bridged a lot of ground between libertarians and merely pro-business, chamber-of-commerce Republicans; “foreign policy conservatives,” who chiefly focused on anticommunism; and “social conservatives,” who addressed a spectrum of concerns about culture and morality. The arrival of the neoconservatives in the 1970s, who had some attachment to all three camps, can be seen as providing new crossbeams between the legs. There was always friction, and sometimes open fighting, but like any coalition they had enough in common to stay together — especially on Election Day.

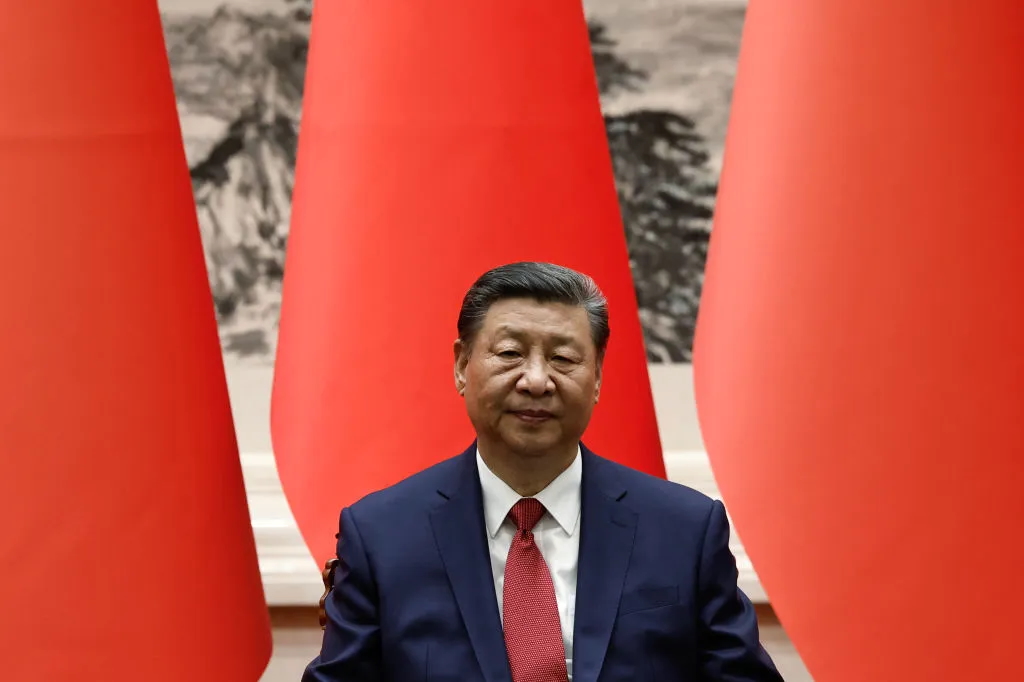

Neither libertarianism nor neoconservatism is identical with, or sympathetic to, what the left means by “neoliberalism,” which adds to the continuing confusion. What they have in common with neoliberalism, at least in part, is a cosmopolitan disposition that dilutes their attachment to America as a singular or exceptional cause. After 9/11, neoconservatives were eager to use American power to spread democracy and remake the Middle East, leading to wars as ruinous and costly as Vietnam, with even less strategic rationale. The libertarians’ attachment to maximized open markets and individual liberty, sound in the abstract, led many of them to support open borders everywhere, heedless of the practical realities of unlimited, self-selecting immigration, legal or otherwise. Libertarians have been equally slow to perceive how the salutary principles of free trade, open markets and globalization have been hijacked by big corporations and the “international community” (think the World Economic Forum and the European Union) to aggregate more political power and authority.

The disharmony between the “enlightened” opinion of the transatlantic elite and the interests of the middle class gave birth to national conservatism, whose two main points are that the democratic nation-state — not transnational political bodies — is the political unit of greatest importance, and that the health of the middle class should be the primary focus of social policy, not simply wealth maximization.

Beyond what national conservatism opposes, and what it supports, lie several difficult problems that must be worked out. Start with politics. In the 1980s, conservatives heaped scorn on Walter Mondale, the Democratic presidential nominee, for daring to suggest America needed an “industrial policy.” Then, it was simply a code phrase for centralized economic planning, if not outright socialism. Now, some leading national conservatives propose “industrial policy” to shore up basic manufacturing. Could the late vice president have been a Republican today? Even more astounding is that some of the natcon thinkers are suddenly warm to labor unions, even seeing a possible policy precedent in…Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. These are truly strange times.

The problem of trade is equally vexing. It is correct that “free” trade agreements like NAFTA were far from true free trade, as Adam Smith or David Ricardo would surely recognize, and that liberalized trade has contributed to hollowing out America’s industrial heartland. But it is far from clear that tariffs or any other form of protectionism can work; indeed, there is good evidence that President Trump’s halting steps in this direction were counterproductive. Needless to say, there are a lot of policy details to be worked through. But the fact is that the natcons are much more friendly to the use of government power than at any time in the history of modern conservatism.

The intellectual debates behind these practical policy problems are even more challenging. Behind the orientation toward the middle class lies a series of noisy debates. The well-grounded natcon rejection of identity politics ran into rough water recently with the announcement that the popular podcaster Dave Rubin, a gay conservative convert from the left who has spoken at natcon events, was adopting a newborn child with his partner. This did not sit well with Declan Leary, who wrote at the American Conservative:

This is evil, plain and simple… The same people who make a living being outraged that Lia Thomas, who is a man, is allowed to swim in the women’s races for his college cannot turn around and tell us that there’s nothing wrong with two dudes having babies together. Is there a difference between men and women, or is there not?

Yet a number of leading natcons (or at least natcon fellow travelers) are gay, such as Peter Thiel (like Rubin, he’s in a same-sex marriage) and Douglas Murray. Moreover, Thiel self-identifies as a libertarian, in contradiction to the principal contention above, though a close look at his rich synthesis of René Girard and Leo Strauss suggests the label doesn’t really fit. Still, his rousing keynote address at the first natcon conference in 2019, which attacked China and the tech industry, was conspicuously silent on the issue of immigration, a key concern of most of the attendees. The natcon movement could fracture over the question of how it should resist the sexual identity politics central to the cultural left.

Ascending the metaphysical ladder, there is a related question of the place of religion in American life, and doubts about the Enlightenment. The older conservative movement before and during the Reagan-Thatcher era saw itself as a branch of the Enlightenment liberal tradition (despite some lingering misgivings), stretching back to the thinker who has been called the philosopher par excellence of America, John Locke. Yet leading natcon thinkers, especially Patrick Deneen and Yoram Hazony, directly challenge this well-settled account of America. According to this view, the principle of individual autonomy at the heart of the liberal tradition is the source of our problems. Hazony, who is Jewish, argues in his recent book The Virtue of Nationalism that America needs to reject its Lockean understanding and become a self-consciously Christian nation.

To restate the thesis, the point of national conservatism is that limited government is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a healthy free society. Tax cuts and deregulation will not restore stable families and a secure middle class, nor revive America’s cultural cohesion and self-confidence. Even more than the feisty conservative movement that came together in the 1950s, or the “new right” that emerged in the 1970s, national conservatism is going to be deliberately political, and will be the main game in town for the next generation. Fights there will be, but they are the kind of fights that make a movement stronger. The left should be so lucky as to have this sort of internal ferment.