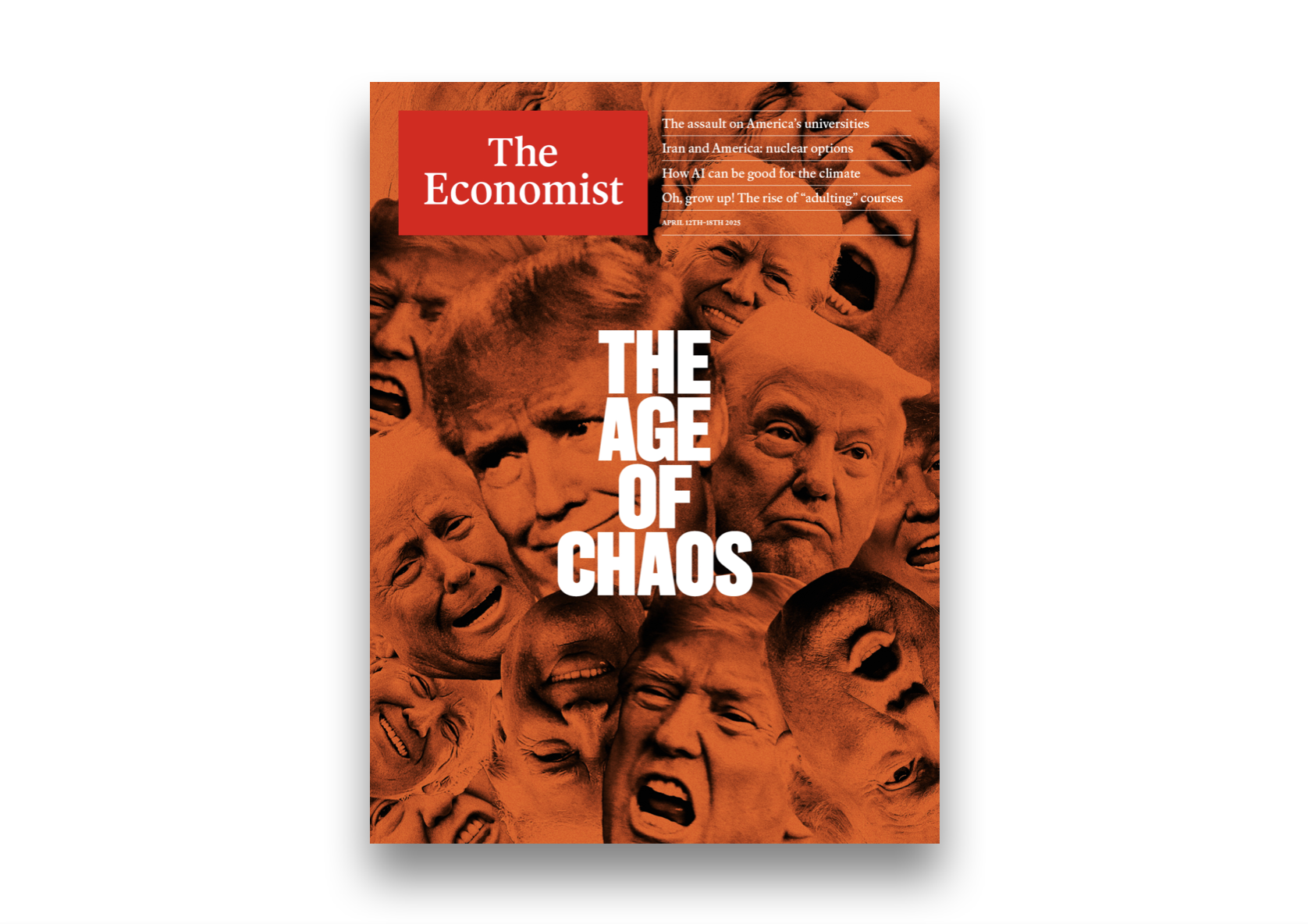

Anthony Scaramucci, Donald Trump’s former director of communications, has a phrase that sums up his old boss’s effect on political debate: “the universe bends towards him.” In the US, discussion about this year’s election is all about Trump. But he is exerting the same gravitational pull in Britain, both on the Tories as they face opposition, and Labour as it mulls the likely dilemmas of government.

Trump is resentful of those who have been ‘nasty’ about him: this includes nearly everyone in the Labour Party

Theresa May offers a case study in how not to deal with Trump. As Britain’s prime minister hoped to befriend him and acquire some kind of post-Brexit trade deal. But her efforts yielded nothing more than excruciating photocalls (“He ran rings around her,” says one former government aide). Her team still grimace at the time Trump believed their phone call had been cut off, when it was still going. “It wasn’t pleasant,” recalls a May era aide. Boris Johnson had a little more luck. During the 2019 general election, he used flattery to convince Trump that he shouldn’t comment on British politics when he was in the country for a NATO summit. Reports of Trump’s unpopularity with the public were rubbish, he said, but Labour wanted to weaponize the president’s visit against the Tories.

What both the Tories and Labour agree on is that The Donald is unpredictable, easily offended and will make life a lot harder for a Labour prime minister than for a Tory one. While aides in No. 10 think Trump’s candidature could boost their electoral chances as voters might opt for stability in the face of likely chaos, most Tories believe Rishi Sunak will not be in Downing Street long enough to welcome the next president. The main debate among Tories is the potential Trumpification of their party in opposition.

Liz Truss set the ball rolling with her recent appearance at CPAC, the US conservative conference that has become a Trump love-in. Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist who ran his 2016 campaign, asked her if her premiership was brought down by the Economist and the Financial Times. “These are the friends of the deep state,” she replied. It was an unusual spectacle. Truss’s excuse is that she was there to promote her upcoming book Ten Years to Save the West.

Still, her attempt to come up with a populist version of the Reagan-Thatcher axis worried many in her party. She suggested to Bannon that he “come over to Britain and sort out Britain” once he was done fixing America. Nigel Farage, she added, should become a Conservative member and do his bit. “It was embarrassing for all involved,” says a former minister.

While Truss spent plenty of her interview criticizing pro-Palestine protests, back in the UK Lee Anderson used a GB News interview to go further. He said that “Islamists have got control” of Sadiq Khan, who had given London to “his mates.” Some see his consequent suspension from the party as representing a deeper power struggle. Anderson, a former coal miner, is a Tory grassroots favorite. It’s no coincidence that the members of parliament defending him the loudest are ones who tend to argue for a more Trumpian approach. Jacob Rees-Mogg has suggested Anderson should have kept the whip. Suella Braverman is understood to take the view that Sunak went too far in suspending him. All this is teeing things up for a debate about the future of the right.

“Liz and her allies would like us to be Trump-lite,” says one Tory member. Right-wing Tories argue the political landscape changed after Brexit, so there is no space for reheated Cameronism. Instead, the party should take inspiration from right-wingers around the world who are winning. “It’s more ‘Britain first’ but lower case,” says one member.

The fear among those on the left of the party is that the right-wingers could gain momentum if Sunak leads the Tories to a heavy defeat, particularly if much of the debate takes place on the US-style GB News, where Anderson hosts a show for $125,000 a year. However, a One Nation member tells me: “No polling suggests Britain is polarized in the same way as the US… The only way any party will win is in the center ground.”

As Tory tribes prepare for an ideological fight after the general election, Labour has to work out how to deal with President Trump. Normally the UK and US get along well, no matter who is in the Oval Office or No. 10. But Trump is famously resentful of those who are, as he puts it, “nasty” about him: this includes Keir Starmer and nearly everyone in the Labour Party. Labour’s putative foreign secretary, David Lammy, described Trump as a “racist Ku Klux Klan and Nazi sympathizer” and went so far as to take part in a protest against his state visit to Britain.

Still, the bar for Anglo-American diplomacy has been set reassuringly low by Lord Cameron, who in his new role is not excelling at making friends and influencing people. In his memoirs, Cameron said Trump’s victory represented the triumph of “protectionist, xenophobic, misogynistic interventions.” As if to remind everyone that foreign policy was not his forte in No. 10, he wrote an article for the US press a few weeks ago saying that if Congress did not support aid to Ukraine it would be like the “weakness displayed against Hitler.” One Trump ally responded by telling him to “kiss my ass.”

Lammy is now on a mission to befriend. I understand Ben Judah, author of This Is London, has left his role on Washington’s Atlantic Council to join the Labour team. Judah worked at the American conservative think tank the Hudson Institute, and has ties to both Republicans and Democrats.

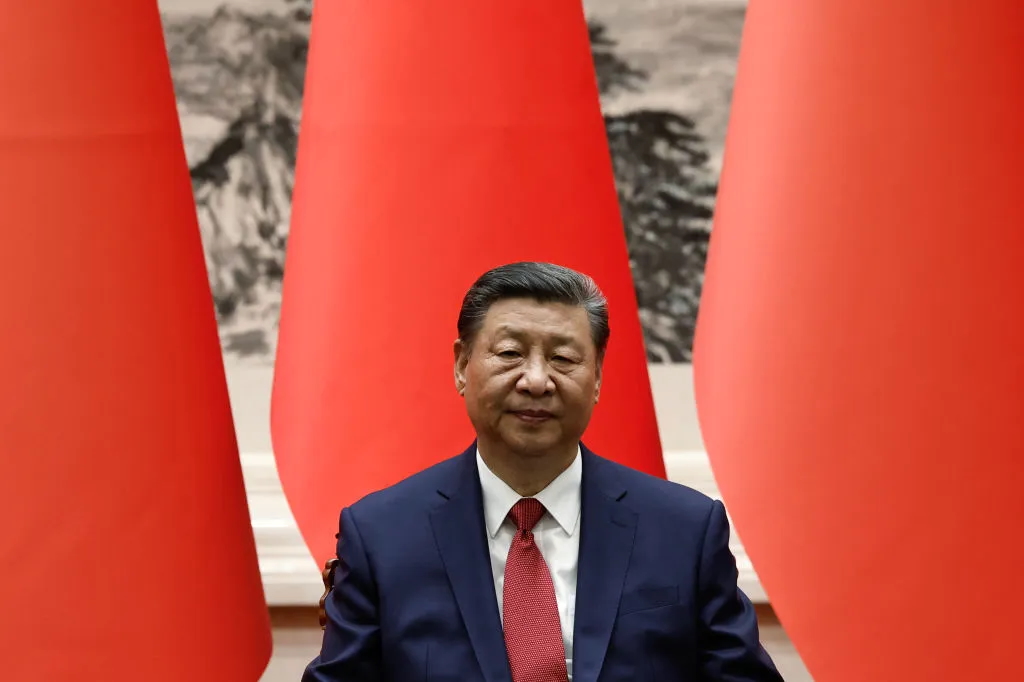

The shadow foreign secretary has also been meeting those tipped to be in Trump’s second-term team, including Elbridge Colby, a former Pentagon advisor and leading China hawk, and Robert C. O’Brien, who has been mentioned as a possible secretary of state, and JD Vance, the Ohio senator tipped as a potential running mate. And at the Munich security conference, Lammy had dinner with Mike Pompeo, Trump’s last secretary of state.

Many around Trump are skeptical about sending arms to Ukraine. The aim of Lammy and Starmer will be to will be to find a middle ground by agreeing that Trump is right about Europe needing to invest more in security and defense. Questions about whether the UK would lead by example, and how, remain unanswered.

The general idea is that if a Starmer-Trump relationship does misfire, Labour will have other lines of communication open to them. But if Starmer and Lammy go too far in their Trump charm offensive, it will be the Labour base who sees red.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply