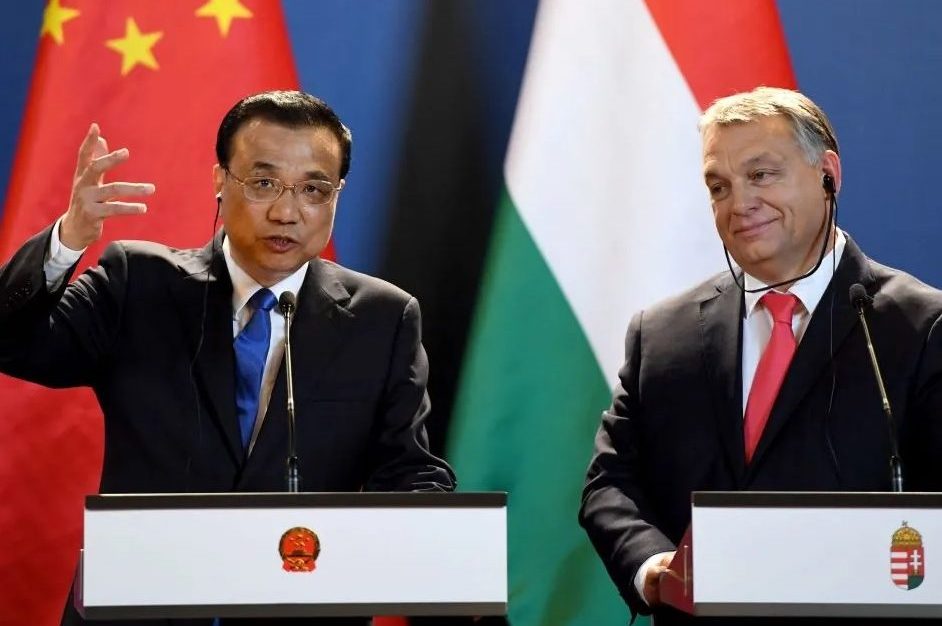

This week a security deal was announced that could see Chinese police on the streets of Hungary. Despite this, there was remarkably little fanfare about the agreement — just a few vague details in public statements made days after the deal was signed between the interior ministers of the two countries. Yet is represents another troubling challenge by Hungary’s authoritarian leader Viktor Orbán to both NATO and the European Union, of which he remains an increasingly troublesome member.

The security pact will involve “enhancing cooperation in law enforcement and joint patrols,” according to the Hungarian statement, while the Chinese version said the two countries would, “deepen cooperation in areas including counter-terrorism, combating transnational crimes, security and law enforcement capacity building.” It appears to be modeled on an arrangement with Serbia (which is not in the EU), where Chinese police jointly patrol areas popular with Chinese businesses or tourists.

Hungary was the first EU country to join China’s troubled Belt and Road Initiative, an umbrella program for Chinese infrastructure investment overseas, and more generally for extending its influence. Budapest has vigorously courted Chinese cash — even as Brussels has grown increasingly wary, urging members to “de-risk” their relationship with Beijing. The country is home to Huawei’s biggest logistical base outside China, and CATL, a giant Chinese battery maker, plans to build a $7.7 billion plant near Debrecen, the country’s second largest city.

BYD, an electric car maker, has also announced plans to build an assembly plant in Hungary, even as the EU is investigating Beijing’s vast government subsidies to EV makers, which it suspects of dumping their vast excess capacity overseas at below cost.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]These investments have not been uncontested in Hungary — which may explain the relatively low-key announcement of the security pact. There have been protests in Debrecen against the battery plant, sparked by concern over pollution and the pressure on local water resources. There were also protests in Budapest against plans to build a campus of Shanghai’s Fudan University at a cost of $1.8 billion, which now appears to have been shelved. Concerns were raised about academic freedom and the loss of land earmarked for student accommodation. The mayor of Budapest renamed several local roads, creating “Uighur Martyrs Street,” “Dalai Lama Street” and “Free Hong Kong Street.” Opposition politicians have also criticized another Chinese project, a multi-billion railway linking Budapest and Belgrade, claiming that it is overpriced and riddled with cronyism in the awarding of contracts. Though few of these controversies get wide coverage in the Hungarian media, which is tightly controlled by Orbán.

It has long been Chinese Communist Party policy to drive a wedge between Europe and America, and in a narrow sense its investment in Hungary has paid dividends, since Orbán has faithfully blocked the EU from issuing communiques criticizing human rights abuses in China and been a drag more broadly on security-related affairs, such as the expansion of NATO and support for Ukraine, which also serve Beijing’s wider security interests.

The CCP will play up its relationship with Orbán — a statement from China’s State Council this week claimed the new pact would, “make law enforcement and security cooperation a new highlight of bilateral relations” and that they were “building a new type of international relations.”

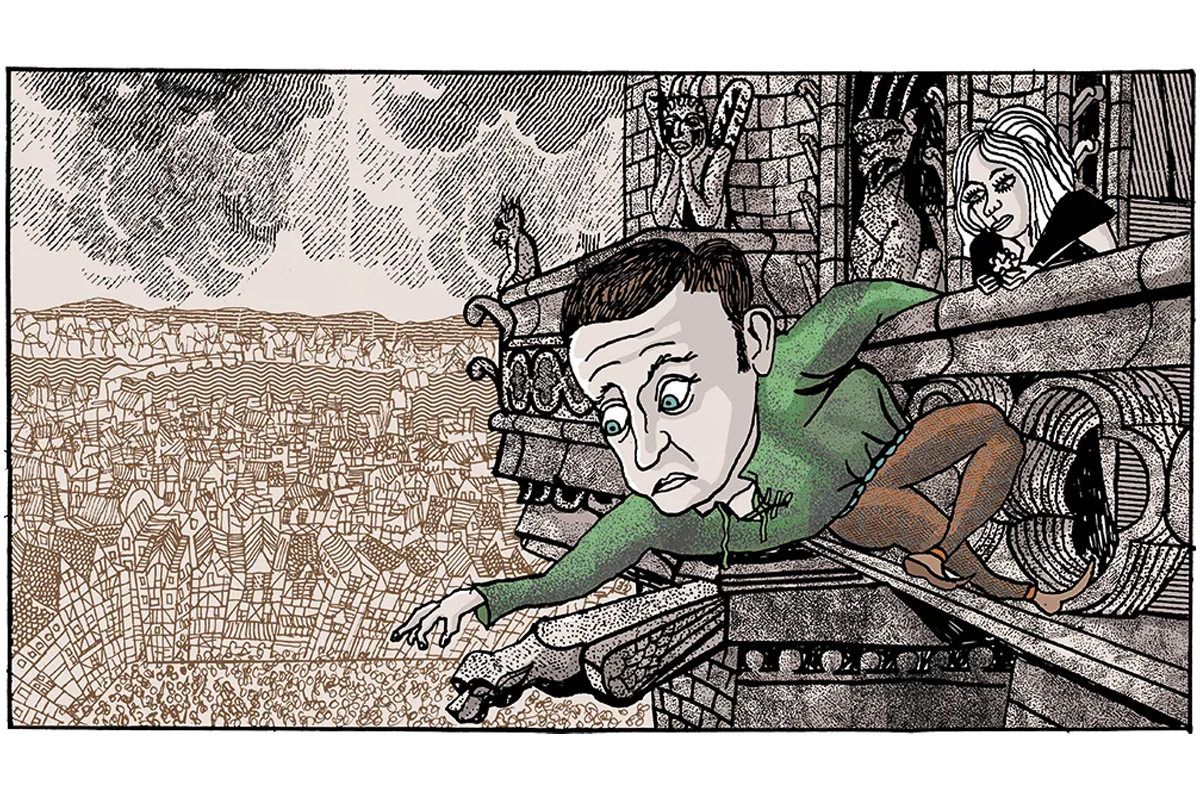

The reality is that Orbán is increasingly an outlier in Europe. China’s main instrument for extending its influence among central and eastern European countries was what it described as the “17+1” format, encompassing those countries plus China. It has become increasingly zombified, steadily losing members and influence, largely because of the CCP’s own behavior — its often heavy-handed interference in domestic politics and its failure to deliver on economic promises. Though the biggest reason for the mood change against Beijing in Europe lies in the CCP’s support of Vladimir Putin and his brutal war in Ukraine, which has done more than anything else to open European eyes to the reality and dangers of Xi Jinping’s China.

Perhaps the biggest blow to Chinese ambitions in Europe came shortly before Christmas when Italy pulled out of the BRI. Italy had been the only member from the G7, and defense minister Guido Crosetto said signing-up had been “an improvised and atrocious act.” Italy’s main criticism was that it simply hadn’t delivered, but Crosetto also voiced concern about Beijing’s “increasingly assertive attitudes.” Italy also briefly hosted Chinese police, the country having the biggest Chinese resident population in Europe. But this was stopped after revelations of a network of undercover police stations across Europe, which were being used to pressure alleged “fugitives” to return home — fugitives being an extremely elastic term in China.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Xi is now wheeling his Trojan horse into Budapest, welcomed by a fellow authoritarian, but Europe is now better prepared. Beijing’s foothold has been slipping elsewhere in a Europe that is more wary of CCP influence — and of the increasingly wearisome antics of Viktor Orbán.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply