When I try to write a letter by hand, my hand has forgotten how to do it. I stumble at the end of words. I trip over letters I’ve known since I was five. It’s odd, too, because writing by hand is what I do. I am paid to letter the titles of books and draw offbeat, sophisticated hand-lettering for advertisements. I am a professional handwriter and I am losing my grip. Have I become obsolete or is it the pen?

Writing manually has become abnormal. I now think onto my laptop’s screen via an arrangement of letters on a keyboard, an arrangement originally devised to insert a steadying difficulty into the typing sequence to protect the typist from speeds that might be dangerous. At one time it was believed that speed was dangerous, but now speed is the elixir.

I am never at a loss for words, electronically. The neatest trick of all is that I have my collected works with me all the time, in a laptop the size of a child’s picture book. I carry it with me from room to room or down the street to my neighborhood café, where I can see how brilliant my words seem after I’ve ingested some caffeine or a glass of wine, or three glasses of wine, or a highball, or a glass of water imported from Italy. When I close the laptop everything disappears and I cease to exist as a writer and artist. If I ever lost this simulacrum of myself, I would disappear.

A few years ago, a real estate agent in Chicago bid at an auction of abandoned property and purchased a box full of photographic negatives. The trove turned out to be only a fraction of an immense collection of photographs taken by an unknown photographer. A non-person. After considerable digging he learned that she was Vivian Maier, an eccentric who did housework for people and tended their children so they could lead their own unbothered and more important lives. She was a photographer in the most private and invisible sense. She almost never printed her photographs, never sold them, never showed them to anyone. There is no privacy like poverty.

On her days off, this nonexistent genius left the houses where she worked and lived, with her grade-school charges in tow, her Rolleiflex camera around her neck. She shot everything: people on the street, drunks with their careful dignity, businessmen with their blank looks, children crying. She never spoke of her art to anyone. Thousands of rolls remained undeveloped at her death, and she died as invisible as her work. From self-portraits caught in store window reflections and mirrors, she appears to have been a very ordinary-looking woman in a slouchy hat and a raincoat, as nondescript as a spy.

It made me wonder. Would anyone know about Vivian Maier today if she had used a digital camera? Nobody would know her name. Nobody knows about nobodies anymore: you have to declare yourself. Flickr and Tumblr and Facebook and Instagram are our photographic archive: massive storehouses of sunsets, puppies, selfies, photos of restaurant meals and strangers’ genitalia, photos you hope to use to embarrass a friend someday, endless catalogs of primping, clowning and dining, self-invention and self- destruction. What does this say about us?

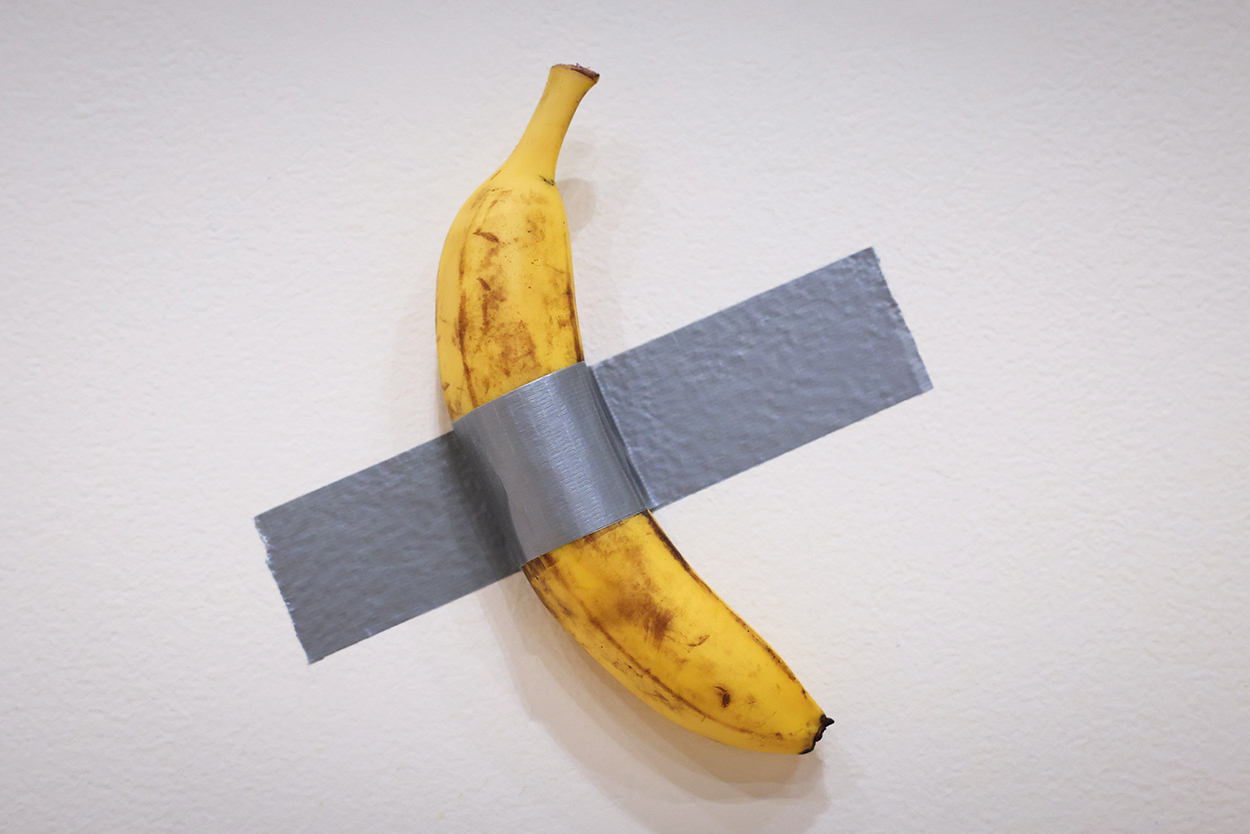

In our modern world everybody is an artist. Everyone is a writer. A billion filmmakers deliver free amusement on YouTube, TikTok and Facebook. The curators of the virtual museum are the commenters: “U R brilliant! :)” We don’t seek the validation of editors and critics. They know art, but do they know us? And if they did see inside us, would they “like” us? Without critics and curators, we face a flood of words and images with no sense of what to save and what to throw away.

Will it keep? In the twentieth century, we worried about acid in the paper and how sunlight fades color photographs. This has been replaced with abstract worries about binomial code and the health of the server. Each time we upgrade the program or platform, the previous archive becomes obsolete. Millions of ideas and memories are jettisoned, often forever, lost as surely as the masterpieces buried or incinerated in war.

The compensation is brief ubiquity. Photography is everywhere because cameras are everywhere. No landscape or tragedy, however private, is safe from photographic capture and instant worldwide distribution. But preservation is uncertain and the lifecycle of the modern photograph is like a mayfly’s. Three years ago, it would have been on iPod touches or flash drives. Those are now antiques. We now store everything on The Cloud. But what if it rains? What if the sky is suddenly empty? Even our ancient libraries are on electronic life support. You can look closely at things in the Vatican Library or the British Library or the Prado without going to Rome or London or Madrid, without getting close at all.

We are failing to curate the present. New artists are unpaid because the internet is free. The journals and libraries that once curated mass culture are being starved. Money is the final arbiter, and its best device for distilling quality from quantity is the auction house of social media. If true artists emerge in this brave and careless new world, they glow briefly before being abandoned for the next novelty. You will never be in a crowd experiencing art at the same time in the same place. You will share the idea of art with strangers in thumbnail form, until the next item chimes its arrival. We exist electronically now. But if we exist everywhere online, do we exist anywhere at all?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2022 World edition.