We bemoan autocracies in Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, Russia and China but largely ignore the more subtle authoritarian trend in the West. Don’t expect a crudely effective dictatorship out of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: we may remain, as we are now, nominally democratic, but be ruled by a technocratic class empowered by greater powers of surveillance than those enjoyed by even the nosiest of dictatorships.

The new autocracy rises from a relentless economic concentration which has engendered a new and fabulously wealthy elite. Five years ago, around four hundred billionaires owned as much as half of the world’s assets. Today, only one hundred billionaires own that share, and Oxfam reduces that number to a mere twenty-six. In avowedly socialist China, the top one percent of the population holds about one-third of the country’s wealth, up from 20 percent two decades ago. Since 1978, China’s Gini coefficient, which measures inequality of wealth distribution, has tripled.

An OECD report issued before the Covid pandemic finds that almost everywhere, the non-rich share of national wealth has declined. These trends can be seen even in social democracies like Sweden and Germany. In the United States, as the conservative economist John Michaelson put it succinctly in 2018, the economic legacy of the last decade is “excessive corporate consolidation, a massive transfer of wealth to the top 1 percent from the middle class.”

This process has developed both in the tangible and digital economies. In Great Britain, where land prices have risen dramatically over the past decade, less than one percent of the population owns half of all the land. On the European continent overall, farmland has fallen increasingly into the hands of a small cadre of corporate owners and the mega-wealthy. In America, the largest farmland holder is Bill Gates, with over 200,000 acres, while Ted Turner and John Malone preside over lordly estates of over two million acres each — larger than several American states.

As property has concentrated, small-holders have come under increased pressure. Australia historically has enjoyed high rates of homeownership, but the rate among twenty-five to thirty-four year-olds dropped from more than 60 percent in 1981 to only 45 percent in 2016. The proportion of owner-occupied housing in once-egalitarian Australia has dropped by 10 percent in the last twenty-five years. Morgan Stanley predicts that the US will soon become primarily a “rentership society” where Wall Street firms seek to turn homes, furniture and other necessities into rental products.

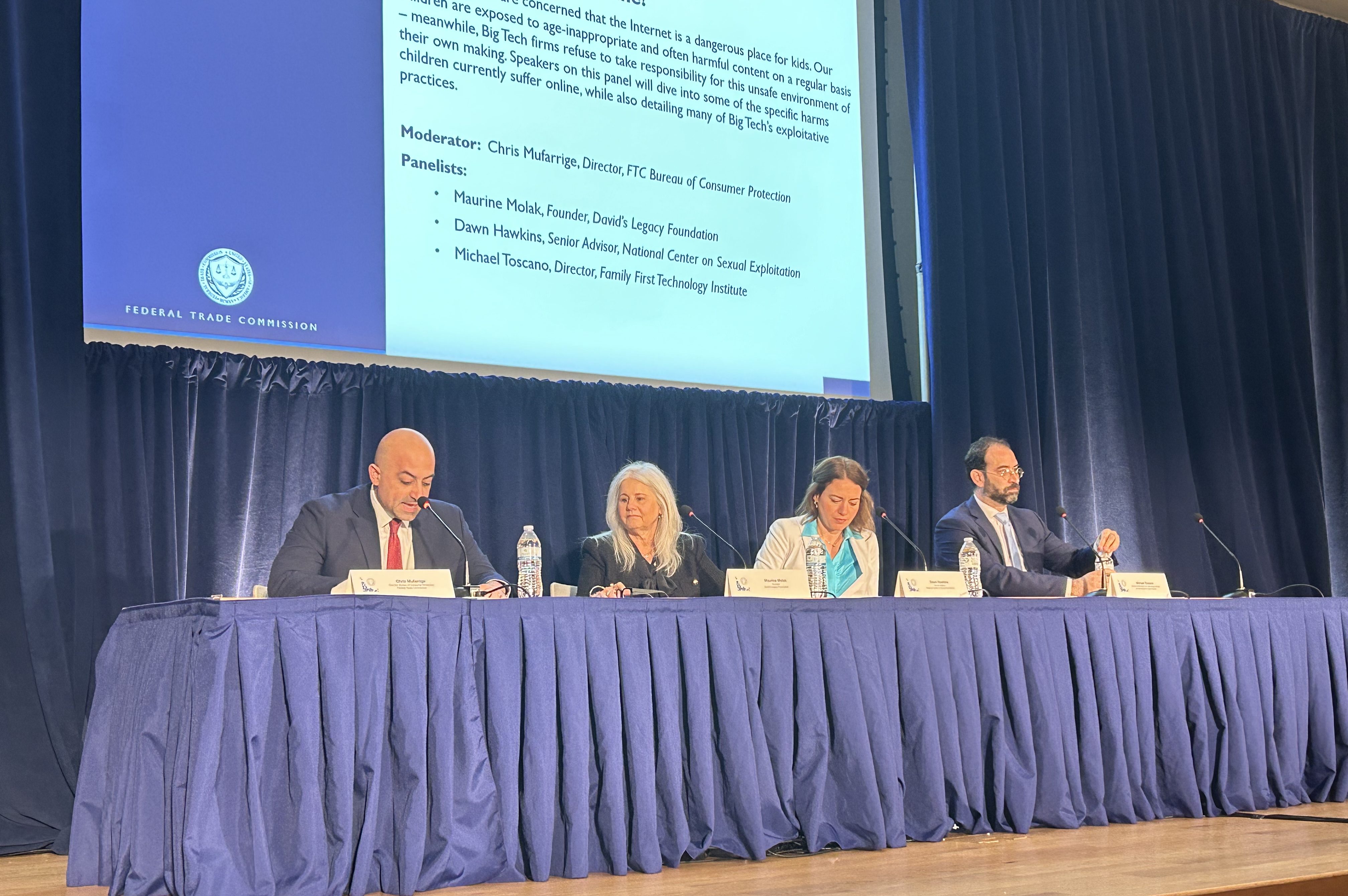

The digital economy is similarly dominated by a small group of giant firms. These overlords together exercise control of up to 90 percent of critical markets such as basic computer operating systems, social media, online search advertising and book sales. No longer satisfied with controlling the pipelines, the tech oligarchy increasing buys up old news outlets and “curates” the news to its tastes. It increasingly dominates mainstream entertainment too: the pending sale of MGM to Amazon is just the most recent example of its conquest and consolidation of the means of communication.

Like the barbarian princes who shaped the Middle Ages, the new oligarchs have been able to seize their fiefdoms with little resistance from weak central governments. The pandemic accelerated this process; its lockdowns and restraints on mobility proved a bonanza for tech companies like Google, whose profits doubled during the period. In this highly regulated environment, the tech-rich have simply gotten richer: seven of the ten richest Americans come from the tech sector. Apple, by some calculations, is now worth more than the entire oil and gas industry. The already obscenely rich have become richer still. Jeff Bezos alone saw his net worth jump by an estimated $34.6 billion in the first two months of the pandemic, while his company has enjoyed continued revenue and profit growth.

As executive compensation reached the stratosphere in Big Tech and finance, small businesses face what the Harvard Business Review calls “an existential threat.” Experts now warn that one third of small businesses, which comprise the majority of US companies and employ nearly half of all workers, could ultimately shut down for good. Hundreds of thousands have already disappeared, including nearly half of all black-owned businesses. Particularly damaged have been the small merchants along Main Street and those working for them, such as restaurant and hospitality workers.

The old middle class struggles to compete with online platforms. Amazon is able to coerce small businesses to give up their data. As big-box stores have done for decades, Amazon uses its bargaining power to minimize supply-chain issues by leasing its own ships and using its considerable leverage to secure items that smaller companies cannot get. Property is seeing a similar consolidation. As middle-class prosperity falters in Britain, cash-rich Lloyd’s Bank seeks to gobble up the emerging market in distressed properties, apartments and even single-family homes. Meanwhile, the grand houses of central London are restored to Victorian opulence by absentee Russian, Chinese and Arab investors.

Climate-change policies could nurture the new autocracy for a generation. As tech oligarchs and the financial establishment implement the Davos notion of a Great Reset, they will force a quick end to fossil fuels. There are huge opportunities for massive investment by super-rich companies and speculators in the “green economy,” all made possible with tax breaks, loans and guaranteed sales to governmental units.

This promises to create a new crop of mega-billionaires like Elon Musk, today the world’s richest man. In the era of super-subsidies, a wannabe electric-vehicle maker like Rivian, which has negligible sales and consistent losses, can be valued higher than General Motors, which sells almost seven million cars and has $122 billion in revenues each year. In Green Capitalism, the British Marxist James Heartfield labels this “austerity socialism”: reaping governmental edicts as opposed to actually producing real goods. Nice work if you can get it.

For the middle and working classes, however, the Great Reset may prove somewhat less promising — if not disastrous. For most people, notes Eric Heymann, a senior economist at Deutsche Bank Research, the rapid “green” transition will mean “a noticeable loss of welfare and jobs.” The conscious policy of degrowth as a means of forcibly reducing greenhouse gas emissions will require getting most people out of their cars, and forcing them to travel far less and to live in tiny apartments. Enforcement will be necessarily intrusive as well. Planners in the UK and elsewhere are pushing for family “carbon budgets.” Add surveillance technology and we end up with something akin to China’s “social credit” system, in which your right to free movement is subject to government approval.

The young are particularly threatened by these changes — younger people already face much harder prospects than any postwar generation. Few expect things to improve: across the higher-income countries, roughly two-thirds of people surveyed by Pew Research see a poorer future for the next generation. According to researchers at the Equality of Opportunity Project, about 90 percent of those born in 1940 grew up to earn higher incomes than their parents. The same is true for only 50 percent of those born in the 1980s. A recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis warns that millennials are in danger of becoming a “lost generation” in terms of wealth accumulation. To make matters worse, over half of all young people, in a survey of ten countries, think the world is doomed by climate change.

As housing and other costs skyrocket, class lines are hardening. Inheritance as a share of GDP in France has grown roughly threefold since 1950, with some upper-income French millennials inheriting more money than many workers make in a lifetime. The growing importance of inherited assets is even more pronounced in Germany, Britain and the United States. In the US, a country with a national mythology that looks askance at inherited wealth, the children of property-owning parents are far better situated to own a house eventually (often with parental help) and enter what is now known as “the funnel of privilege.” In America, millennials are three times as likely as boomers to count on inheritance for their retirement. Among the youngest cohort, aged eighteen to twenty-two, over 60 percent expect that inheritance will be their primary source of income as they age.

How will the downwardly mobile react to the prospect of permanent rental serfdom and, ultimately, total dependence on the state? A recent Edelman survey reveals that increasing numbers no longer trust institutions or believe hard work pays off. In a world dominated by a few institutions, today’s precariat of gig and short-contract workers, and those who have dropped out of the workforce entirely, could become an economically less useful version of Marx’s proletariat: a permanent underclass requiring aggressive, quasi-military policing.

Meanwhile, large tech firms and financial giants — even those skeptical about climate change zealotry — see the prospect of record profits and valuations in “disruption.” The pandemic accelerated the white-collar shift to remote work, and the broader demand for automated solutions skyrocketed. A future less reliant on human labor elevates the tech oligarchs to the highest perch on what Lenin called “the commanding heights” of the economy.

In a digitalized economy, it’s good to control the critical niches. The oligarchs do this brilliantly. They have seized dominant shares of key markets from search (Google) to social media (Facebook) to book sales (Amazon). Google and Apple together provide over 95 percent of operating software for mobile devices, while Microsoft still accounts for over 80 percent of the software that runs personal computers around the world.

I have covered Silicon Valley for forty-five years. Today, it is less the hypercompetitive, free-spirited place I knew, and more like the early twentieth-century trusts. Mike Malone, who has chronicled Silicon Valley as deeply as anyone, sees it losing much of its ethos. The new masters of tech, he suggests, have shifted from “blue-collar kids to the children of privilege,” and moved away from the production ethos that once made the Valley so inspiring and egalitarian. An intensely competitive industry has become enamored with the allure of “the sure thing” backed by massive capital and sometimes by government. Competition is no longer a spur to creativity: competitors are simply bought out.

Wealth cannot rule on its own. Autocracy needs a proselytizing class who can justify the rulers and salve the distressed souls of the lower orders. In medieval times, the Catholic Church served this role, essentially justifying the feudal order as the expression of divine will. Today’s version, a sort of clerisy or intelligentsia, is mostly not religious and consists of people from the upper bureaucracy, academia, and the culture and media industries.

The pandemic has been a boon to this class too. The emergency allowed governments to grant them unprecedented executive and administrative powers not just in centralized France but even in usually semi-sensible Great Britain and Australia. For some, the lockdowns served as a “test run” for necessary measures to realize their preferred climate-change policies. In the new schema, the real class enemy is not the excesses of the ultra-rich, or even wasteful spending by government: it’s the consumption patterns of the masses. We see this in the response of progressive media and even politicians such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortes to complaints about the rising costs of food, rent and energy. The clerisy sees even the essentials as ephemeral, and supply-chain problems as the consequence of too much consumption by the masses.

As in the Middle Ages, when church and crown competed for moral and political authority, the bureaucratic and unelected sources of power are not always in agreement. But to a large extent, they embrace very similar ideologies, particularly when it comes to imposing control over information about the pandemic or climate change. The early-twentieth-century Italian sociologist Robert Michels noted that complex issues — climate, for instance — reinforce what he called the “iron law of oligarchy”: the more dependent on expertise a society becomes, the greater the need for elite-driven solutions that bypass popular input — and the greater the force the elite will apply to attain its goals.

H.G. Wells dreamed of a “new republic” run by a virtuous few. Our digital elites are anointing themselves, and being anointed by their fellow elites in business and media. Well-educated managers of major companies and the credentialed clerisy are naturally drawn to the idea of a society ruled by professional experts with “enlightened” values — that is, by people much like themselves.

To confront what they see as an existential crisis, much of the media supports the creation of a global technocracy. “Democracy is the planet’s biggest enemy,” asserted an article in Foreign Policy, an establishmentarian journal, in 2019. This hostility to democracy as an obstacle to top-down “progress” is dovetailing with another source of anti-democratic distrust. People around the world, particularly the young, no longer embrace the basic notion of self-government. A majority of young Americans now favor large-scale government intervention in the economy; about a third call themselves socialists.

The leaders of woke capitalism have signed onto a pledge to defund fossil fuels in the great quest for Net Zero. This is not, as the wacko right and the wacko left might think, a conscious conspiracy. Instead, it is propelled by tech firms’ natural desire for profits derived from replacing the carbon-spewing analog world wherever possible, and the irresistible lure for investors and corporations of a huge, subsidized and government-financed market.

Most tech and finance executives are not ideologues. Nor are they, despite appearances, sociopaths. Yet they feel justified in censoring and even demonetizing not just Donald Trump or the New York Post or Bari Weiss, but also the credentialed experts whose views diverge from the accepted line for staffers at Google, Facebook and Twitter, organizations where woke instruction is increasingly imposed. (These companies’ location in the San Francisco Bay Area and the Puget Sound region, two of the most lopsidedly progressive areas in the country, is also a factor.) Many firms espouse woke ideas, says Jim Wunderman, president of the Bay Area Council, because they are “afraid of their own employees.”

In practice this often means eliminating conservative opinions — and not just views from the crazy fringe, according to former employees. Academic experts such as Judith Curry and Roger Pielke, with somewhat contrarian takes on climate, are routinely ignored, attacked and marginalized. Skeptics like the long-time environmentalist Mike Shellenberger, the Obama advisor Steven Koonin and the “skeptical environmentalist” Bjorn Lomborg are largely consigned to the social-media memory hole for detailing the environmentalists’ record of exaggeration, hyperbolic projections and immiserating policies.

We are increasingly ruled by a perfect marriage of class convenience, with more power for the clerisy and ever-greater economic opportunities for the oligarchy — all with the added benefit of encouraging them to feel good about themselves. Even as they push austerity on the masses, they live like medieval lords, indulging in lavish weddings and building estates reminiscent of the Habsburgs’. Jeff Bezos just spent $100 million on a Hawaiian retreat. Bill Gates’s daughter just enjoyed a $2 million wedding. John Kerry, President Biden’s chief climate scold and beneficiary of an heiress’s fortune, travels on a private jet that use thirty times the energy of the average American vehicle.

That’s fine. The anointed purchase “environmental offsets”: a green version of indulgences. This may make them feel better about their vast wealth and excesses, just as it did for the murderous and corrupt aristocrats of old. Still, many are also making preparations against a potential peasant’s revolt — just in case. This includes using private security, building bunkers and looking for remote boltholes in the US or abroad, notably in out of the way and strictly controlled New Zealand.

What is the end game for the oligarchs and their clerical allies? Upward mobility for the masses is out of the question. The technology journalist Gregory Ferenstein has interviewed 147 digital company founders. His conclusion: “An increasingly greater share of economic wealth will be generated by a smaller slice of very talented or original people. Everyone else will come to subsist on some combination of part-time entrepreneurial ‘gig work’ and government aid.” In Silicon Valley’s estimation, the mass of people can look forward to life as subsidized consumers of Facebook’s metaverse or Google’s dream of “immersive computing.”

What will the rest of us do? There is clearly some disenchantment with the emerging order. Global trust in institutions, most notably the media and Big Tech, has fallen to a low ebb, and economic and geopolitical insecurity are on the rise. We are trying to impose a green economy that we don’t have the technology or even the electricity to power. This will force some countries to return to coal — China has stepped up its use of coal-powered stations — and others to leave part of their populations to shiver.

As blue-collar and many white-collar jobs are eliminated by automation, the oligarchs and their allies in the clerisy want to impose a Universal Basic Income, to keep the peasants from suffering too much and possibly rebelling. We have already seen pushback from the right and left in both Europe and America. Many people do not want to accept a life of subsidized dependency, made bearable by the digital equivalent of Rome’s bread and circuses.

The time could be shorter than we think. The tech oligarchs are creating something similar to what Aldous Huxley called in Brave New World Revisited a “scientific caste system.” There is “no good reason,” Huxley wrote in 1958, that “a thoroughly scientific dictatorship should ever be overthrown.” It will condition its subjects from the womb so that they “grow up to love their servitude” and “never dream of revolution.” It will maintain a strict social order and provide enough diversion through drugs, sex and videos to keep their artificially narrowed minds occupied and sated.

The fusion of government with large oligopolistic companies, and the technologically-enhanced collection of private information, allow the new autocracies to monitor our lives in ways that Mao, Stalin or Hitler would have envied. A rising tide of money and administrative power defines the rising autocracy. If we as citizens, whatever our political orientation, are not vigilant, our democracy will become an increasingly hollow vessel.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.