While the Taliban continues to double down against women in Afghanistan, the UN appears to be wanting to normalize relations with them. Women in the country are already blocked from almost all jobs and all education. Yet a week after the extremist group barred females from working for the UN, the organization’s deputy secretary general Amina Mohammed said it was now time to take “baby steps” towards “recognition (of the Taliban).”

As UN spokespeople tried to limit the damage, protests poured in from Afghan opposition groups. One statement from a wide group of Afghan artists and human rights activists slammed nearly two years of “futile regional and global diplomacy” since the Taliban took Kabul in 2021. At a conference in Vienna this week to form a united opposition movement to the Taliban, the leader of one of the main groups fighting against them, Ahmad Massoud, told me he was “outraged” by Amina Mohammed’s comments. Recognition would mean “giving in to an armed extremist group and getting nothing in return.”

There is clearly chaos at the heart of the UN over what to do next

The Taliban urgently want their control of Afghanistan recognized in order to fully participate in relations with the outside world. But they have done nothing to encourage outsiders to believe that they might move towards a more inclusive government.

Afghan democratic activists fear that they are, once again, being ignored while the world legitimizes the Taliban. They are pressing for inclusion at a meeting in Doha on Monday between the UN secretary general António Guterres and envoys for Afghanistan from countries across the world.

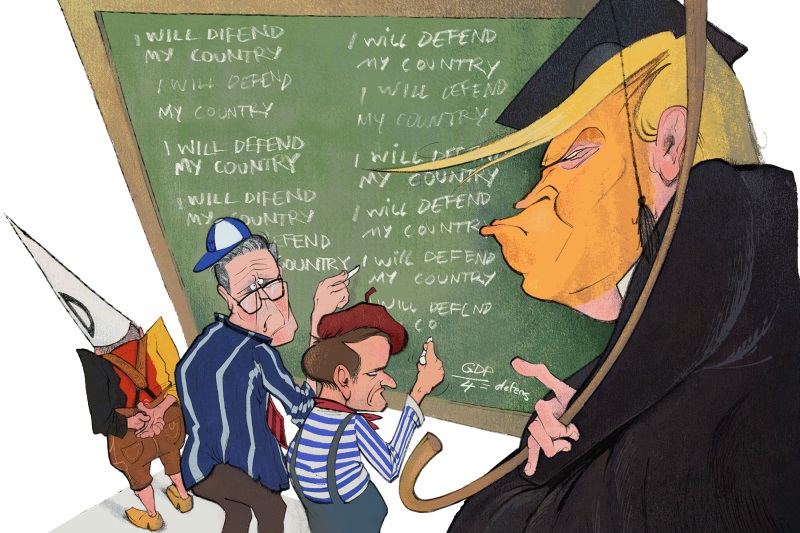

Despite formal denials, some suggest organisers of the meeting in Doha might indeed be under pressure from some countries to take those “baby steps” in a pragmatic and cynical move to accept the reality of Taliban rule. Fawzia Koofi, a former MP, and one of the few women members of the government team for the failed peace talks with the Taliban in 2021, said that some western countries who claim to have a “feminist foreign policy” are now failing to support Afghan women when it really counts. Britain would likely back recognition of the Taliban if it came to a vote. And there is mounting pressure to recognize the Taliban from elsewhere: Russia, China, Pakistan and more recently Turkey have exchanged ambassadors and established more normal relations with the Taliban, while not formally recognizing them.

Nargis Nehan, a prominent women’s rights campaigner and former minister, said that instead of recognition, the international community should take a harder line, impose financial sanctions and travel bans, and persuade Qatar to close down its safe haven for the families of leading Taliban figures. The international community has little leverage to make the Taliban behave better, but making life harder for its leaders may focus minds.

There is clearly chaos at the heart of the UN over what to do next. The dilemma of how to deliver aid is acute. The humanitarian imperative is to save lives, but also to work within certain norms, which include being able to employ women at least to work with women, if not to have equal employment rights.

Afghanistan remains on life support with 28 million people needing help and talk of a famine this spring. But while humanitarian principles demand a response, there are tough decisions ahead. We may be making life too easy for the regime. The former MP Fawzia Koofi said that continuing food aid means the Taliban can use revenues for the security forces, while “the international community feed the people.”

There are 3,300 local staff working for the UN in Afghanistan, including 600 Afghan women. They have been at home on full pay this month since the Taliban made the announcement that women could no longer work for the organization. Most other aid organizations have already had to cut nearly all programs except basic food supplies.

And while the UN consider options, public messaging is all over the place. After the reverse ferret over the remarks of the deputy secretary general, a spokesperson also had to deny a comment quoted in the Guardian from the head of the development program, the UNDP. Achim Steiner had said that they may have to take the “heartbreaking” decision to pull out as early as next month because of the difficulties of working under the conditions imposed by the Taliban.

As well as food aid, the Taliban receive around $40 million a week to keep the economy afloat. They put pictures of shrink-wrapped bricks of cash as it arrives on social media, to show they are connected with the world and apparently doing something for people.

Recognition is a blunt instrument, the “largest tool in the box” according to the former Afghan foreign minister Rangin Dadfar Spanta. “Once used it cannot be repeated.” But while the world grapples with the problem of recognition, potential democratic groups opposed to the Taliban are gathering without UN or government support.

The meeting in Vienna this week bringing together former ministers, women activists and fighters, was privately sponsored. It aims to build a larger umbrella group in the coming months, united in opposition to the Taliban, and standing for an Afghan republic based on fundamental principles giving rights to all.

So far it is a tiny green shoot. It would not cost much to bring it to life and support a united opposition to the Taliban. The alternative — grudging recognition of the regime, and incremental collapse of the country as the economy implodes and the Taliban fight among themselves, is not attractive.

The historical parallels are not encouraging. We know how this ends. The world has ignored Afghanistan before, in the 1990s, and that led to 9/11.

But for now it looks as if another betrayal of the Afghan people is on the way. “The US sold our country through a peace deal,” said Nargis Nehan, “and now the UN is sacrificing the whole population of Afghanistan just to keep their operations going.”

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.