We have all seen a sign, usually in a mom-and-pop business, declaring, “We reserve the right to refuse service to you.” In a free society, it is hard to argue with this assertion. Shouldn’t a business owner, landlord, or proprietor have the right to decide whom to serve to and whom to decline to serve? This is the essence of the freedom of association, which includes the reciprocal right to refrain from association.

Or does it?

In Colorado, cake artist Jack Phillips was threatened with draconian legal penalties for declining to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple due to his religious objections to such unions. In 2017, the Supreme Court granted Phillips a reprieve from his ordeal, but the litigation continues. A similar case, also from Colorado, was argued in the High Court this week, involving a devout Christian woman, Lorie Smith, who designs custom websites but objects to creating websites to celebrate same-sex weddings, which she opposes on religious grounds. The state of Colorado seeks to force her to engage in what she regards as objectionable speech, or else.

As a bookend to the issues presented in that case, styled 303 Creative v. Elenis, a Richmond restaurant, Metzger Bar & Butchery, last week abruptly canceled a reservation for a private event a mere 90 minutes before it was scheduled to begin, when servers discovered that the patrons were associated with a group, the Family Foundation, that opposes abortion and same-sex marriage.

The restaurant explained (emphasis added), “We have always refused service to anyone for making our staff uncomfortable or unsafe, and this was the driving force behind our decision. Many of our staff are women and/or members of the LGBTQ+ community… We respect our staff’s established rights as humans and strive to create a work environment where they can do their jobs with dignity, comfort and safety.” Many segregated restaurants (and schools) in the Jim Crow South made that same argument in favor of their exclusionary policies.

This type of incident has become increasingly common, especially in “woke” areas inhospitable to conservatives. In 2018, a party that included then-President Trump’s press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders was asked to leave a restaurant in Lexington, Virginia, in the middle of their meal because the owner and wait staff (several of whom were gay, according to the owner) were offended by Sanders’ politics.

Are restaurant evictions subject to the same legal standard as the Colorado wedding vendors, i.e., does the freedom of association control the outcome? Unfortunately, the answer is no. There is a double standard at work here. Because of civil rights legislation enacted in the 1960s, private businesses are no longer free to discriminate on the basis of “protected characteristics,” which initially consisted only of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. (The freedom of association continues to exist for non-protected characteristics.) Many people opposed such legislation precisely due to the resulting abridgement of the freedom of association, an outcome that the Supreme Court upheld in a pair of cases decided in late 1964.

To vindicate the rights of black Americans, therefore, the right of businesses to deny service on the basis of race was banned to eliminate the scourge of segregation. Only proponents of Jim Crow, and constitutional purists such as Senator Barry Goldwater, quarreled with this result.

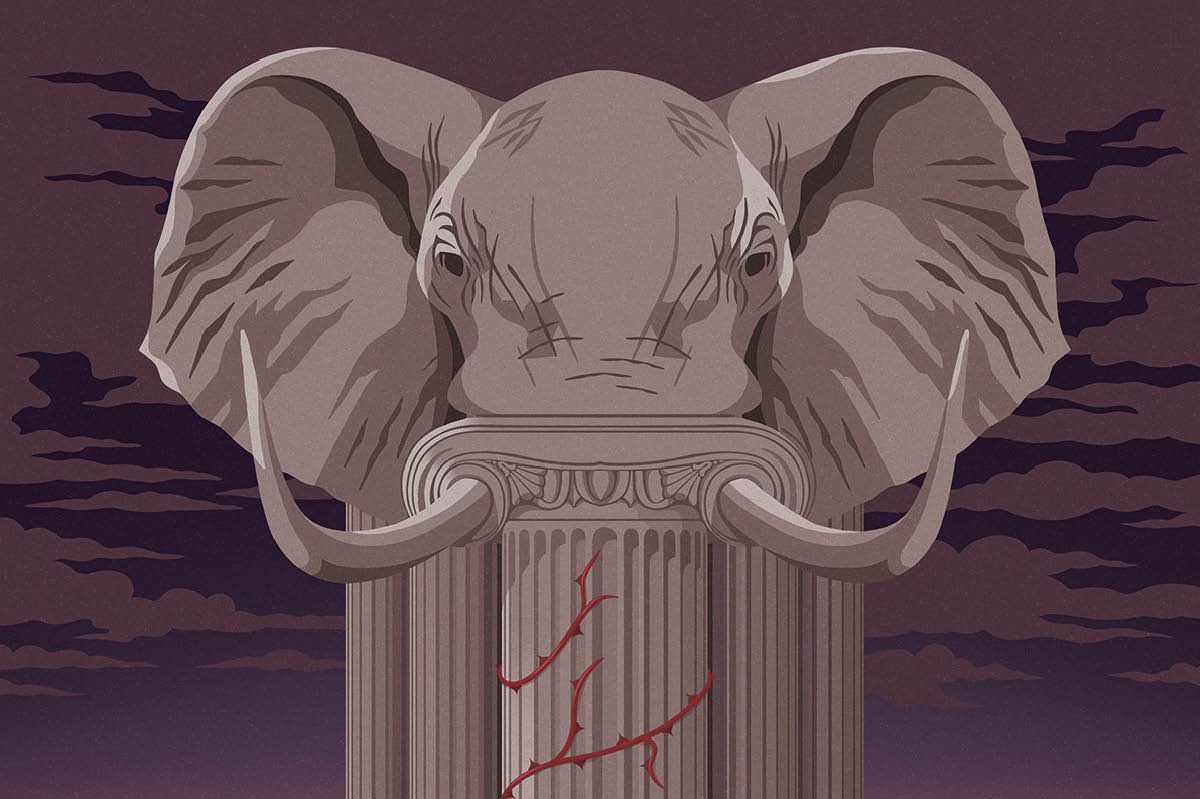

So things stood — largely without controversy — for about 50 years, until identity politics and the culture war expanded the categories entitled to “civil rights” protection. Anti-discrimination statutes, at both the state and federal levels, were supplemented to include additional “protected characteristics,” often adding sexual orientation, gender identity, and transgender status. Such “civil rights” laws, of which Colorado’s is an example, became a potent weapon in the hands of litigious LGBTQ advocates, who equate opposition to same-sex marriage (a right “recognized” by the Court in the 2015 Obergefell decision) with race discrimination.

Because state and federal civil rights laws do not contain an explicit exception (or defense) for religious objectors, business owners wishing to refrain from endorsing same-sex unions (by making cakes, creating websites, etc.) must defend themselves under the rubric of the First Amendment, claiming either compelled speech or a violation of their religious beliefs — a protracted, expensive, and uncertain undertaking fraught with the risk of catastrophic legal liability.

Meanwhile, because political ideology, partisan affiliation, and Christian morality are not considered to be “protected characteristics” under existing civil rights laws, woke businesses are free to boycott, cancel, and evict conservative customers at will, subject only to the penalty of public opinion and the marketplace. The Red Hen, the restaurant that booted Sarah Huckabee Sanders and her party mid-meal, reportedly faced some immediate fallout and briefly closed, but did not experience any long-term consequences.

Identifying as LGBTQ is not equivalent to race, and opposition to same-sex marriage is not the same as racial bigotry. Millennia of Judeo-Christian tradition support sincere, good-faith opposition to the recent innovation of gay marriage. The current culture war has much more nuance to it than whether lunch counters should be integrated. It is a mistake to include sexual orientation in the blunt instrument of anti-discrimination laws applicable to private businesses, which can have the disastrous effect of eliminating their freedom of association.

Some may urge that conservatives join the parade of victim groups seeking civil rights protection. But the real solution is less — rather than more — coverage for such intrusive and easily abused laws.