Statues must fall. Bronzes must be ‘returned’. The artifacts in question are the famous ‘Benin bronzes’ taken by the British from the royal court of the Kingdom of Benin in 1897. The present demand is that they be returned to Nigeria; confusingly the kingdom’s former territory is now part of Nigeria, not the modern day Republic of Benin. In 2016 Jesus College, Cambridge announced it would be discussing the return of a bronze cockerel. In May, Germany agreed in principle to the return of the Benin objects in its public collections — Germany holds nearly 300 of the most prized items. In June, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art stated it would be returning two plaques.

With the Benin bronzes (which are actually made of many different materials) we have a useful exemplar of the fashionable narrative of dastardly colonialist deeds by dead white European males. The fact that the objects were taken from a West African kingdom that could hardly be confused with a pacifist, vegan commune — Benin grew rich on the Atlantic slave trade and the slaying of elephants; it practiced human sacrifice and possibly ritual cannibalism — does not quench the appetite of those demanding their return. Moral taint only seems to apply to westerners.

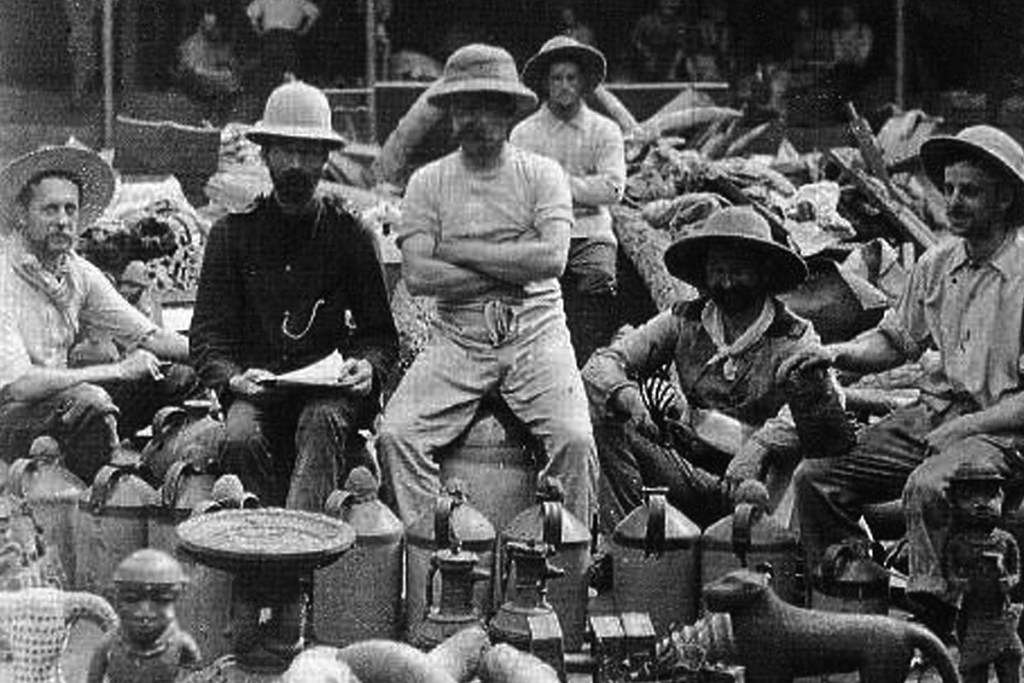

In January 1897 James Phillips, the acting consul general of the British territory of the Niger Coast Protectorate, led a party of nine white colonial officials and 250 or so African porters to the Kingdom of Benin. They were ambushed. Four of the colonialists, including Phillips, were killed and a further three either died in the ambush or after being taken prisoner. Many of the African porters were killed.

In retaliation the British launched a punitive expedition against the kingdom. British forces captured Benin City and the palace of the oba, or king, on February 18, 1897 and the territory of the kingdom was incorporated into the British colony that would become Nigeria. The oba’s palace and other ceremonial buildings were richly ordained with ornate ivory carvings and bronzes predominantly dating from the 16th century onwards. These were taken, along with a huge quantity of uncarved ivory, by the British forces, with the justification that the sale of these items would defray the costs of the expedition. In truth, many of the looted items ended up in the private possession of the British officers leading the expedition.

By September 1897 a selection of the bronzes were already on display in the British Museum. That items of such quality and refinement should have come out of what was perceived as a primitive society generated astonishment. Today, items taken from the Kingdom of Benin are on display in over 160 Western museums, 38 of them in the United States — at the Met and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, in the collections of Harvard and Yale universities, and elsewhere.

The Kingdom of Benin controlled trade in certain goods through its fetish priests placing a magical juju on them. This placed the goods outside the sphere of everyday items and, importantly, the bounds of normal commerce. A similar ritual taint has been placed on the Benin bronzes, this time not by fetish priests but by Dan Hicks, professor of contemporary archaeology at Oxford and curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum — the university’s ethnographic collection. Hicks has called for the return of the Benin bronzes. In his tract The Brutish Museums (selected by the New York Times as one of its Art Books of the Year), he also demands ‘the physical dismantling of the white infrastructure of every anthropology and “world culture” museum’.

The Kingdom of Benin, right up to its downfall in 1897, held slaves and practiced human sacrifice. Even Hicks — a strong partisan for Benin and its oba — acknowledges these shortcomings. The Brutish Museums asks ‘what then became…of the Oba’s harem, slaves and servants’ after the British conquest — i.e., it acknowledges that there were slaves in Benin in 1897. Hicks goes on: ‘It is continually left vague how many deaths represented human sacrifice and how many were casualties of the British attack’ — i.e., he acknowledges that human sacrifice was practiced there. What is left for debate is how many of the 1897 dead were killed in human sacrifice and how many were casualties of the British raid. The Kingdom of Benin was a slaving state and grew rich on the back of the Atlantic slave trade. It captured other Africans and sold them to European slave traders. Hicks acknowledges this: ‘The Kingdom grew in power and scope during its involvement in European and transatlantic trade from the 16th century, at first with Portuguese traders, and later British and French — central among which was the slave trade.’ There is some debate as to the relative importance of the slave trade versus the trade in ivory — not exactly seen today as a noble undertaking either. What is clear is that slaving was at least as important to the rise of Benin as it was to the rise of Britain, and very probably considerably more so.

The very metal used to make the Benin bronzes, coming from horseshoe-shaped manillas manufactured in Europe, was obtained by the kingdom in exchange for slaves. The Benin bronzes are every bit as much an expression of the wealth created by slavery as a plantation house in the American South or an English stately home built on the proceeds of West Indies sugar estates. Yet Hicks and his fellow returnists attach no moral opprobrium to these West African artifacts, while no tour of a tainted house can be completed without acknowledging its founding sin.

Few today would want to argue that the Benin bronzes were initially legitimately acquired — those taken in 1897 were clearly secured without consent. Many Benin objects, including all those in American museum collections, were purchased on the secondary market, either by the institutions themselves or by their subsequent donors. The bronzes that the Met is returning are a case in point. They had been in the collection of the British Museum and were then transferred to the Nigerian National Museum in the 1950s. Some time thereafter, in unclear circumstances — they weren’t formally deaccessioned — they left the Nigerian museum and reentered the market. In 1991 they were bequeathed to the Met. In other words, these particular bronzes had been previously ‘returned’ — and their second return has more to do with their dubious recent history than the events of 1897. Their fate is not the greatest advertisement for restitution.

It is unlikely the major auction houses will again be willing to sell objects taken in 1897. In 2007, Sothebys sold a Benin bronze in New York for $4.7 million. In 2011, Sothebys in London announced that it would sell a Benin ivory mask with an estimate of £3.5 million to £4.5 million but then swiftly reversed the decision and withdrew the lot under pressure from the Nigerian government. The London item had a more problematic provenance than the New York offering: the ivory mask was offered for sale by the descendants of one of the British officers involved in the 1897 expedition, while the New York item was being deaccessioned by the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, New York. When the Albright-Knox bronze was offered at auction it was challenged in the courts, but solely on the grounds of the legitimacy of the museum’s deaccessioning its antiquities and pre-modern works, not on the basis of provenance.

The direction of travel for the Benin bronzes, or at least some of them, is becoming clear. In Benin City there are plans for a new $100 million Edo Museum of West African Art designed by noted British-Ghanaian architect Sir David Adjaye. This is planned as a repository of returned Benin objects. It seems unlikely that their exhibits will be displayed with the same kind of contextualizing plaques you now find in Western museums next to objects with a tainted pedigree.

Meanwhile, the Church of England is ‘in discussions’ with Nigeria to return two Benin busts. The trouble is that these were not looted in 1897, indeed, they were not created until the early 1980s. The objects in question were a gift from the University of Nigeria to the then-Archbishop of Canterbury Robert Runcie, and were freshly minted. Some institutions want to be guilty, even when they have nothing to be guilty about.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2021 World edition.