The notorious Infowars host Alex Jones once opined that he didn’t like the government “putting chemicals in the water that turn the friggin’ frogs gay.” CNBC called this a “disturbing and ridiculous conspiracy theory” — and Jones is noted for wild and sometimes actionable claims.

But if we read “gay” in the colloquial sense, as offensive shorthand for “feminized male,” Jones’s assertion contains a glimmer of truth. Chemicals really are going into the water that so disrupt the endocrine systems of small aquatic creatures, including frogs, that males sometimes undergo sex reversal or adopt homosexual behavior. It’s just that the synthetic estradiol that damages fish and amphibians isn’t being added to the water as a sinister government conspiracy.

The truth is more banal: traces of estradiol are peed into the sewage system by every woman who uses hormonal birth control, and this compound is difficult to remove in sewage treatment. So if you’re on the pill, it’s not the government messing with frogs’ sexual behavior. It’s you.

The catastrophic ecological impact of hormonal birth control is one of the many cognitive dissonances in liberal feminism, a movement that generally prides itself — at least superficially — on alignment with progressive causes including concern for the environment. But the lure of consequence-free sex is so powerful that no matter how often the ecological destructiveness of the pill is reported, this fact somehow never seems to register in the popular consciousness. It’s the only way we can go on viewing as “consequence-free” something that in fact has serious consequences — just largely borne not by humans, but by frogs and fish.

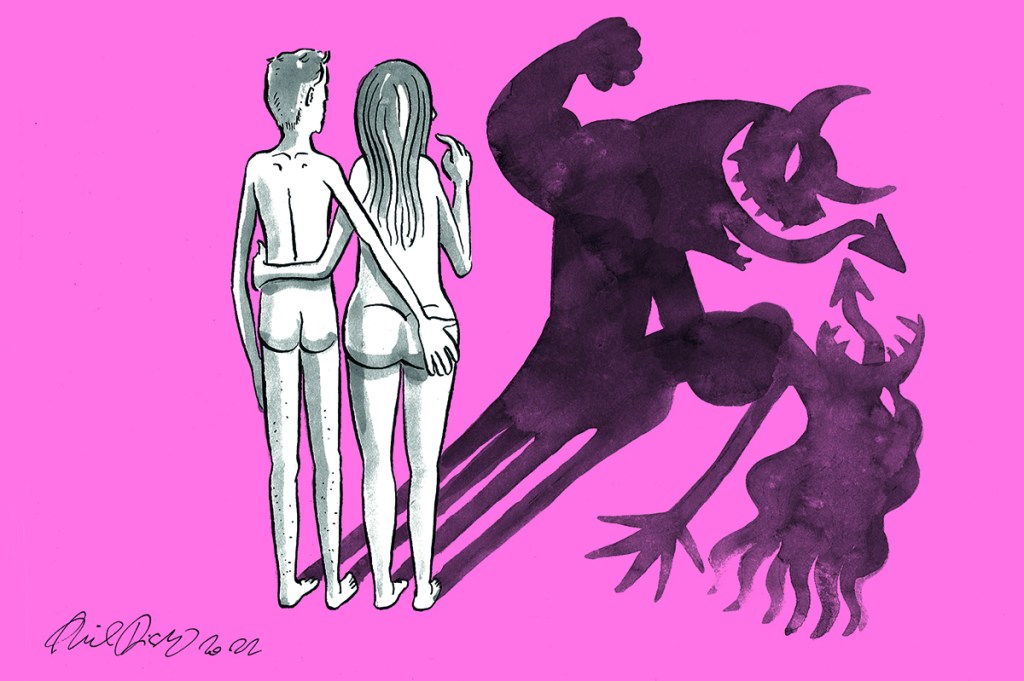

That doesn’t mean there are no consequences for us, though. After fifty years of its reign, the figures are in: the pill’s effect on the delicate social ecology of sexual relations has been every bit as bad. The pill plays a central role in opening the door for a host of figurative poisons, which have percolated into every facet of our intimate relations. And on both ecological and social fronts, many feminists simply choose to look past these side effects, because progress means individual autonomy at any price.

In the view of internet historian Katherine Dee, changing attitudes to the pill stand in for wider concerns about the sexual revolution. Many young women from across the political spectrum, she argues, internalized the contemporary “liberated” approach to sex — but have, as Dee puts it, come to feel they were “duped.”

Increasingly, such women are blaming hormonal birth control for a slew of side effects. They’re looking for alternatives, too: videos with the #naturalbirthcontrol hashtag on TikTok have been viewed more than 30 million times.

On the face of it, the complaints are about biological side effects. But we can also read, beneath this, a broader statement: the pill is making me miserable. And this is a far broader critique. For in de-risking sex, this technology has made it ubiquitous, and in the process stripped desire of anticipation, excitement and mystery: emptied it of eroticism. In its place we’re offered an increasingly coarse, commodified and grotesque landscape of all-you-can-eat lust.

This marketization of sexual desire has been under way now since the 1960s. And digital culture has accelerated the ways we’re able to buy sexual stimulation or sell ourselves as commodities. The resulting hellscape of sexual anomie is the true face of what calls itself “sex-positive” feminism, a movement that doesn’t seem to have prevented Gen Z from slumping into a “sex recession.” Indeed, it may even be driving it. Pornography degrades the capacity for mutual pleasure: Dr. Harry Fisch calls porn “the single, largest non-health issue that makes relationships crumble,” linking porn over-use with erectile issues and inability to orgasm.

This phenomenon is known as “death grip syndrome.” Pervasive digital access to porn is leading to a widespread societal indifference to sexual stimuli. As @gotsnacks_ puts it on TikTok “I’m booty’d out.” Or, in the case of those older women of my generation who were the first to walk into full-spectrum sexual “liberation,” we might say brutalized to the point of no longer wanting to remain silent.

Former Playboy columnist Bridget Phetasy describes this experience in an essay titled “I Regret Being a Slut.” Here, she recounts how when she was younger, “I would have said one-night stands made me feel ’emboldened.’ The truth, though, was that ‘I was using sex like a drug’.” Phetasy reports that she now regrets all but a handful of her youthful sexual encounters, nearly all of which were “either meaningless or mediocre (or both)” and most of which “left me feeling empty and demoralized. And worthless.”

In her view, the greatest damage she did to herself lay in the indifference she cultivated, as a cover for how unhappy it made her feel to be treated as worthless: “I told myself I didn’t care,” she writes. “I didn’t care when a man ghosted me. I didn’t care when he left in the middle of the night or hinted that he wanted me to leave. The walks of shame. The blackouts. The anxiety.” Eventually, she recounts, she hit rock bottom when she received a text message that read “Goodnight baby I love you” — swiftly followed by another that read, devastatingly: “Wrong person.”

By today’s standards, Phetasy and I merely dipped our toes in the shallows of what the sociologist Anthony Giddens called “plastic sexuality.” Since then, the collateral damage has grown steadily worse. The expectations set by free-access porn now routinely result in teenage girls enduring acts they don’t enjoy in exchange for the barest signs of affection. A BBC Scotland survey suggested that over two-thirds of men under forty have spat on, slapped or choked their partner during consensual sex — with many indicating that this was inspired by porn consumption. And fetish practices far more extreme than slapping or choking are now so mainstream that magazines for school-age girls write about “kink” for their youthful readers. This percolates out into real life, with young women on social media recounting experiences of abuse perpetrated in the name of “kink.”

None of this would be possible unless, in the name of freedom and progress, we’d accepted a view of women as sterile by default with fertility as an optional extra. Even for those women who somehow avoid violent or degrading sexual demands, default sterility means continual pressure to accede to loveless sex. The problem Virginia Ironside discovered in the 1960s — that being on the pill made it hard to refuse sex — has only grown worse since, with many women now “consenting” to unwanted sex largely out of politeness.

None of this is in women’s interests. “Liberation” shouldn’t mean violence and casual hook-ups with a 10 percent chance of orgasm. Phetasy now denounces the culture she imbibed, which reduced “sex-positivity” to a promiscuity that left her empty and demoralized. Crucially, she argues: “You can still be sex-positive and accept that for you sex can’t be liberated from intimacy and a meaningful relationship.”

I’m less courageous than Phetasy in describing my own adventures in “liberation.” All I’ll say is that she speaks for me as well. I don’t think we’re outliers, either: as Louise Perry puts it in her 2022 The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: “Loveless Sex Is Not Empowering.” The torrent of acclaim Perry’s book received across the political spectrum suggests that there are many other women out there who feel the same.

We can’t simply stuff the technology back into its box. But we can — once again — lead by example by rejecting it. Don’t take the pill. Don’t encourage your friends to take the pill. Quite aside from harming aquatic life, and facilitating the pervasive pornification of mainstream culture, the pill causes mood issues, weight gain and libido loss. It’s also a crucial precondition for bad sex, because it de-risks casual hook-ups. Why would you take a pill that makes you fat, miserable and sexless?

Objectors may point out that this raises a coordination problem. If mainstream sexual culture now assumes that women will by default be sterile and sexually available, then how is any heterosexual woman who refuses this dynamic ever to find a partner? Won’t men simply pass them over for someone who plays by the usual rules?

Not necessarily. Katie, a researcher from Washington, DC, says that in her experience, dating while refusing birth control was “not at all awkward or weird.” Rather, in her view, it serves to filter out frivolous would-be partners: “If you’re serious about it, and they’re serious and thoughtful too, then it’s not an issue.” That is, the men for whom it’s a dealbreaker are those who anyway only wanted sex: “If they were focused on things that were solely about a physical relationship — sure that’d make it hard.” Katie’s principles have evidently not proved an obstacle to finding a partner: she recently married.

Other objectors might accuse me of trying to legitimize a conservative “purity culture” under the guise of feminism. And it’s true that religious conservatives have long been critical of the pill. But while my reactionary feminist prescriptions — rejecting the pill and casual sex — are similar, I’m not arguing for female “purity” in the sense of imagining that women could or should somehow remain free of sexual desire. Indeed, the “purity” approach seems mainly to incentivize rebellion: Phetasy’s story began with an upbringing in which she was taught to prize this “purity,” to fear sex and to be ashamed of her own desires: “My burgeoning sexuality would unfold as a reaction to these repressive religious orthodoxies, old-school notions of sexual status and trauma.”

I don’t want to re-tread timeworn arguments about some imaginary state of feminine purity. Women get horny. Get over it. We aren’t going to heal the dissociative harms of the sexual revolution by embracing a different kind of body dissociation and faking a “purity” few of us feel.

Instead, we must heal our polluted erotic ecologies by rewilding sex. In the field of conservation, “rewilding” refers to practices such as reintroducing apex predators or reducing intervention in a landscape, such that complex ecologies are able to re-emerge and find equilibrium again. In one famous example, reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the United States resulted, via a complex chain of inter-species interactions, in a river changing course.

Applying a similar mindset to our sexual ecologies means a similar willingness to make space for dangerous elements of the natural order. Specifically, we need to recognize that “risk-free” heterosexual sex can only be had at the cost of reproduction. And eliminating that biological purpose takes much of the dark, dangerous and profoundly intimate joy out of sex.

Pornography itself is a reliable guide to what’s truly forbidden. And the volume of content that now focuses on either the idea of procreation, reframed as “breeding fetish,” or on physical evidence of pregnancy, such as lactation, reveals perhaps that even the most fundamental organismic urge — the drive to reproduce — has not been abolished by opt-in fertility, but merely commodified. If we can reclaim this profound facet of our nature from its capture by Big Porn, we stand a chance of reclaiming the charge, and the intimacy, of sex from a “booty’d-out” culture grown numb to even grotesque stimuli.

But this also means reclaiming the danger. To restore that danger, we must acknowledge that for all but the small minority of same-sex-attracted people, desire and reproduction can’t be disaggregated, any more than “self” and “body.” Shorn of its connection to the source of life itself, that darkness and danger will find twisted expression in depraved fetishes and sexual violence. By contrast, consensual, genuinely consequential sex is profoundly intimate: not least because a woman who refuses birth control will be highly motivated to be choosy about her partners. Pregnancy risk is, after all, a cast-iron reason to reject having sex with anyone out of politeness.

The most direct way for women to reclaim this beneficial sexual self-discipline now is by saying “thanks but no thanks” to the technology. While this means, for those who take this path, an explicit insistence on sex only in the context of trust and intimacy, it doesn’t necessarily follow that women should refuse sex before marriage. But caveat emptor: if you’re playing with this kind of fire, outside the context of a committed relationship, you’d better be absolutely certain you can trust your male partner.

If you are sure of that trust, there’s a strong likelihood you’ll enjoy sex more when you do have it. In a lifelong partnership, the possibility of conception can itself be deeply erotic. And one of the open secrets of “natural family planning” methods is that sex really is better when you don’t disrupt it with artificial hormones. Studies have shown that women’s sexual libido peaks just before ovulation, a cycle that makes perfect sense from the perspective of what sex is ultimately for — but if the menstrual cycle is disrupted by hormonal birth control, this effect disappears. And if you don’t want to conceive a baby, having sex anyway assumes a level of faith in your male partner’s self-control that on its own implies real intimacy.

And along with the pro-pleasure, pro-love case for rewilding sex is the pro-embodiment one. Rejecting birth control is the first and most radical step women can take, in healing the disconnect introduced by technology between us and our own bodies, in the name of freeing us from sex difference. As Abigail Favale notes, relying on cycle tracking to manage fertility increases women’s awareness of our fertility cycles, and with it attunement to our own bodies. In this sense of increasing our agency in terms of fertility awareness, and bringing women into harmony with our own embodied existence, rejecting the pill is not less but more empowering.

The true, deep wildness of sex can only be reproduced, in the sterile order of de-risked consumer sex, by the stylized violence of “BDSM.” Add the real, material “power exchange” of fertility back into sexual intimacy, and I’m willing to bet the popularity of “kink” would evaporate overnight. Or, rather, return to its proper place. In turn, then, we might see fewer incidences of girls passing out in a rear naked choke-hold and fewer incidences of death from “rough sex”; fewer injuries; perhaps also fewer men driven to ever more extreme stimuli in search of the one thing that’s truly forbidden: sex with the real danger left in.

We can have this again. To get there, we reactionary feminists must reject the totalitarian sexual-industrial complex. We can reclaim our sexual cycles, our capacity for eroticism, our attunement to our own bodies, and our right to refuse exploitative, loveless and degrading approaches. And in refusing this degraded parody of our most intimate embodied experiences, we can open ourselves to better ones — not with The One, but with a one: someone who is willing to step up — solidarity, intimacy, family and building a life together.

This is an edited extract from Mary’s book, Feminism Against Progress, which is published by Forum press.