What follows may suggest that I require an “intervention.” Readers might even interpret this column as a cry for help. Please let me assure you that it is not. But I have just learned of a new addiction, and it is possible that I suffer from it.

It is not an addiction to crack cocaine. Nor is it an addiction to alcohol, though I like to think I do my bit. No — it is an addiction I have just learned about thanks to Idris Elba: “Work addiction.”

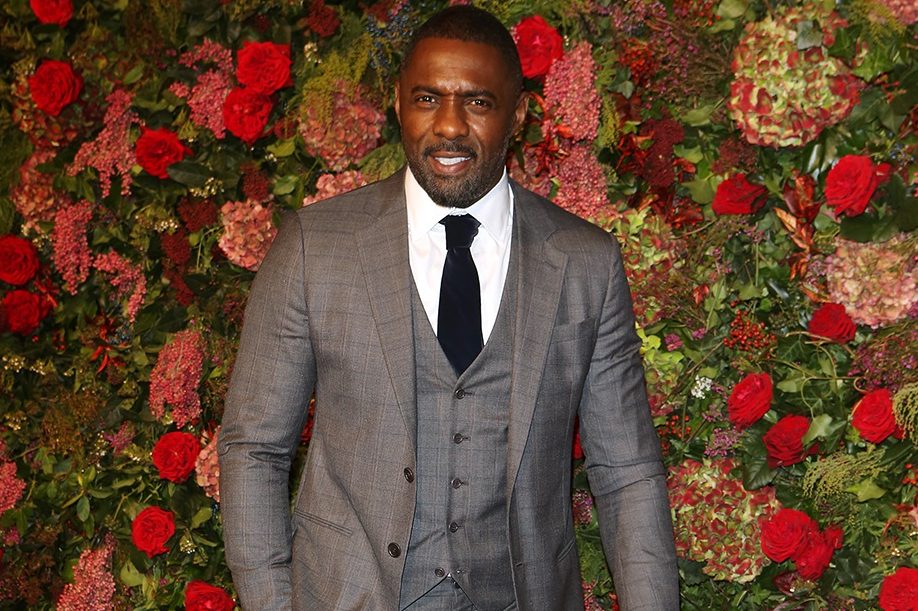

The actor, who you doubtless know from The Wire, Luther and other dramas, gave an interview this week in which he said he has been in therapy for the past year because he is a “workaholic.” After seeing a therapist he has realized his addiction to work is “unhealthy.”

The fifty-one-year-old complained that he often finds it more rewarding to work for ten days straight on a film set than to sit on a sofa with his family. I’m quite sure that it is.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Elon Musk’s fortune has not been amassed through him taking great chunks of ‘me time’

The trouble is that Elba went on to say that the industry he is in “enables” this behavior. I should think it does. Industries often do reward people who work hard. According to Elba, he is in fact “massively rewarded” for working hard in this industry.

At this point the sympathy of some readers might start to dry up. Not least because in this era, while there is no reward for just shutting up and getting on with things, there is always some reward for giving interviews where you confess to having problems which you are “addressing.” That generally means addiction. If you are a celebrity who has been caught putting a hand on someone’s thigh, you can claim you suffer from a “sex addiction” and that you need to go to rehab. But the idea that doing very highly paid work that is also highly rewarding should be regarded as an addiction seems new to me.

There are workaholics, and there always have been. Why does this have to be pathologized, other than for the fact that everything in our era is?

It makes me wonder whether I have a work addiction. It’s possible. For the first seven years of my career I never took a vacation. But then you don’t when you’re starting out. Even now I work almost every day, and when I am not writing I am reading or researching. Even if I am reading something trashy and low-brow, I still have a pencil to hand in case there is something that could be useful. I have no special aversion to sofas, but remain a slightly difficult person to take on vacation. I can spend a couple of days on a beach but soon start to grind my teeth and look for something to do.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]I suspect that a lot of people are the same. And, without shoving myself into their league, most successful people I have ever encountered certainly are.

For instance I have come across few successful people who have built successful businesses who are not in some sense always “on.” Their children and grandchildren are often excellent at relaxing. But that is because someone in the family before them happened not to be. I suspect that Elba’s children will find that their own path in life will be very significantly smoothed — whatever they choose to do — because their father worked hard and was well rewarded for it.

The most obvious such case is the world’s richest man. Elon Musk’s fortune has not been amassed through him taking great chunks of “me time.” And while his domestic life may have been tricky at times, that probably comes as part of the built-in price. The stories that Musk’s latest biographer tells all confirm that he is a workaholic’s workaholic. He knew that if he wanted to motivate his workforce at Tesla he needed to be motivated himself. His restlessness — which is perfectly evident in person — is clearly some part of his success. He doesn’t have time to sit around. And when he needed to sleep on the factory floor because he was working all hours he did so. Was this healthy? Probably not. It must have been bad for his back. But he also created the most successful brand of electric cars to date, and for his next trick he wants to go to Mars. So, again, sofa time for the Musks doesn’t seem like it should be encouraged.

Lots of people do not have this luxury, of course. If you work in a job you dislike in a career you hate then it is easier to avoid being a workaholic. The condition — if that is what it is — only really arises among people who are doing what they love and what they happen to be good at.

In my own small way, I suppose I am guilty of this. I work hard because I love the worlds that I find myself in. Are all the characteristics that come along with this entirely easy for everyone around me? Probably not. A friend from California recently visited and mentioned he had been given some medication from his doctor (inevitably) to deal with his mild irritability. We talked about the medication, how he thought it had helped him in specific work situations and so on. He asked me if I wanted to try it.

I pronounced a hard “no” for two rather obvious reasons. The first was that I suspected that no dosage, however large, would be enough to blunt my intense irritability at almost everything. The second reason, I pointed out (somewhat irritably, I must admit), was that if I started clubbing myself with any such medication I would be out of work within a fortnight. Put me on an anti-irritability drug and I would be writing columns about how nice puppies are and the advantages of spring. It would be occasional columns for Country Life, at best.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]So please do not actually take this as a cry for help. Of course we all need to find balance in our lives. But let’s not club — through medicine or therapy — the people in our society who find their work rewarding. Especially when, as in the case of Idris Elba, it happens to reward so many other people too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.