On a pleasant evening this summer, an ice cream truck planted itself on the corner of my quiet street on the Upper West Side. A few feet away stood a man in his late fifties in khakis and a rumpled button-down shirt. He was busy screaming obscenities at the vendor — the guy I used to call the Good Humor man, but in this case Mister Softee. The issue was that Mister Softee was running his truck’s engine and thus hastening the demise of the planet via global warming.

Where has the cultural license come to behave like this? How did Americans lose their cool?

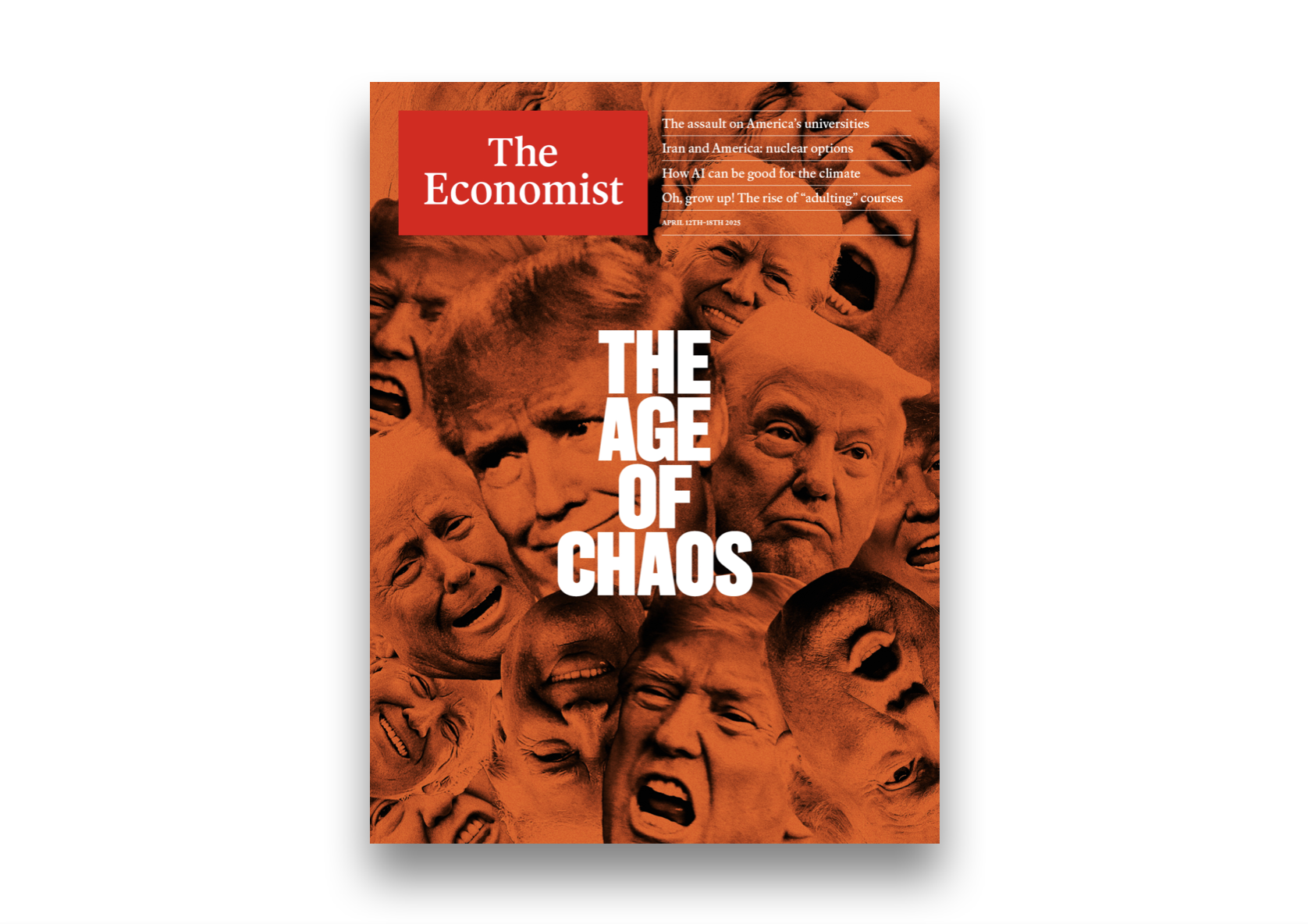

The two most popular answers are Donald Trump and ‘the Resistance’. Both are superficially plausible. The Tweeter-in-Chief has made a performance art of his own anger and enjoys publicly humiliating his foes. His pussyhat wearing, impeachment-obsessed, and Antifa-admiring antagonists, however, have sustained an equally long display of indignation. Either one seems a long way from an environmentalist tirade against Mister Softee, but let’s follow the trail of the dripping cone.

Trump and the Resistance were not the beginning of our national descent into histrionic outrage. The American angriculture began taking shape as long ago as the Fifties, when the inhibitions against public — and private — displays of anger came under assault. The Fifties were the decade in which Freudian psychoanalysis burst into American consciousness and popularized the idea that suppressing anger causes neurosis. No one cites Freud anymore, but most Americans now believe it is ‘healthier’ to unleash their negative feelings than to bottle them up. Actually, those who vent their anger on impulse aren’t healthier. They are just angrier, and evidence has mounted that they have become addicted to rage, which releases its own chemical storm. The more often you express anger, the more you want to.

The Fifties were seminal in other ways as well. Americans discovered existentialism, both the French variety and our domestic brew. This taught us that anger was self-actualizing and a true way to confront the absurdities of life. Anger is authenticating. The great testament to teen anger was published at the beginning of the decade: J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, in which the prep school dropout Holden Caulfield pronounces on the ‘phoniness’ of the adult world and virtually everything else. We learn in the last chapter that Caulfield is telling all this to his shrink. It is the perfect blend of the new Freudian ethic and the existential alienation game.

The Fifties also gestated the Women’s Movement and the Civil Rights Movement, which were discovering other ways to mobilize public anger. All elements — therapeutic, existential, literary and protest-oriented — broke out in much more decisive form in the Sixties. Letting it all hang out wasn’t for everybody. A cultural divide began to open between those who elevated individual expression over traditional social norms and those who clung with growing apprehension to America’s older values.

What those older values might have been is surprisingly contentious. When I published A Bee in the Mouth: Anger in America Now in 2006, the most common criticism was that flamboyant displays of anger were nothing new in America. I called the phenomenon ‘new anger’, but a good many critics pushed back. They said we Americans had always indulged it, enjoyed it and let it run riot.

But that’s merely projecting back on generations that can no longer speak for themselves. America’s contemporary anger mavens misunderstand who we were before we uncorked the anger bottle. It was not that Americans of yesteryear didn’t get angry. We fought a Revolutionary War, a Civil War and quite a few exceptionally nasty elections, beginning with the vituperative presidential battle in 1800 between Jefferson and Adams, served with lots of red-hot-anger sauce. The great difference between anger then and anger today is the public attitude towards its expression.

Throughout most of American cultural history, uncontrolled anger was regarded as a personal weakness, and public expression of anger outside some limited circumstances was regarded as shameful. The high regard in which his countrymen regarded George Washington drew in part from his mastery of his own explosive temper. Washington’s famous ‘dignity’ was achieved by quelling his overtowering anger. What was good for George was good for everyone else. All through the 19th century, the nation’s presses poured out manuals for married couples on how to manage domestic disagreements without descending into anger. Books on childrearing emphasized teaching the young emotional self-discipline. The nation’s literary culture grew up on stories about the destructiveness of uncontrolled anger. Ahab’s quest for vengeance against the great white whale isn’t intended as praise for the captain’s virtuosity in expressing his passion.

The good man in our national mythology was the one who learned to face provocation with cool self-mastery. The good woman too. At one point in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, Jo’s mother, ‘Marmee’, counsels her about her ‘dreadful temper’. She tells Jo that she too had a terrible temper and is still ‘angry nearly every day of my life’. But she has learned ‘not to show it’. Forty years of trying to cure it have only taught her that it can’t be cured, only controlled.

I’m not the only one to have noticed the cultural divide on anger that began to open up in the Fifties. In 1986, psychiatrist Carol Zisowitz Stearns and her husband, historian Peter N. Stearns, published an illuminating book, Anger: The Struggle for Emotional Control in America’s History, in which they traced the intergenerational shifts among Americans starting in the 1700s. The Stearns don’t treat this as a simple before-and-after, as though anger was once all bad and is now all good. By their account, Americans constantly debated how and when to express or suppress anger.

The debate in our era is superficially similar but in fact profoundly different. The briefest way to put it is that Ahab is now the hero. We have learned that anger is self-empowering and that the individual who has mastered the art of look-at-me verbal rage is to be admired. Sportsmanship has been traded for tantrumosity. The internet has spawned a particular form of public shaming known as call-out culture. YouTube sports a whole genre of ‘girl fights’, in which angry young women are caught on camera swinging at each other. Anger has invaded nearly every genre of music from country star Carrie Underwood’s taking her ‘Louisville slugger to both headlights’ to hip-hop star Childish Gambino’s murderous anthem ‘This is America’ and Joyner Lucas’s expletive-filled fugue ‘I’m Not Racist’.

One of the swiftest paths to celebrity these days is a public spat in which the parties attempt to top each other in calumny. Part of Trump’s rise to national prominence was his insult-slinging feud with the comedienne Rosie O’Donnell, 2006–07. After Trump had decided not to fire Miss USA for drug use, O’Donnell, speaking on The View, described him as a ‘snake-oil salesman on Little House on the Prairie’. Trump responded by calling O’Donnell a ’real loser’ and ‘a woman out of control’. In the years that followed the two continued at intervals to revile one another, often gleefully. In 2014, Trump tweeted, ‘Rosie is crude, rude, obnoxious and dumb — other than that I like her very much!’

O’Donnell probably got the worst of this long-term feud because she ended up appealing for public sympathy. In 2014, she declared, ‘Probably the Trump stuff was the most bullying I ever experienced in my life, including as a child. It was national, and it was sanctioned societally. Whether I deserved it is up to your own interpretation.’ And after Trump had derided her in an August 2015 presidential debate, O’Donnell tweeted: ‘Try explaining that 2 ur kids.’

The contretemps continues, each side showering contempt on the other. But is this really anger? It is performative anger: a show meant to entertain, not all that different from a World Wrestling Entertainment match, which not so incidentally has its own Trump connection going back to 1998 when he hosted Wrestlemania in Atlantic City. In 2006, wrestlers wearing Trump and O’Donnell disguises faced off in a WWE match.

Such gladiator fighting is not just all in good fun, but it is among the tamer displays of New Anger. The playfully vulgar version often gives way to a much more heated self-righteous expression of contempt for the opponent. This is the anger that is deeply characteristic both of the ‘Resistance’ to Trump and the Trumpian hatred of the ‘Swamp’. It is an anger that above all wants to be seen and heard. It seems to answer the question ‘Who am I?’ with ‘I’m someone enraged at Trump and everything he stands for,’ or ‘I’m enraged at the criminals who have undermined our democracy by trying to undermine a duly elected president’.

The spirit of mutual annihilation isn’t all there is to contemporary American political culture. Trump has hinged as well as unhinged critics, and the progressive establishment draws sober adversaries as well as ‘Send her home!’ chanters. No one is immune to anger, but we haven’t all descended into collective madness. And surely that’s all that New Anger has to offer in the political space. Anger is a terrific motivator in every sense of terrific. But even a semi-well-ordered republic cannot thrive on terror. How close are we to that dire extreme? Will we stop short of physical mayhem, and if so how short?

Among the bad omens are the masked thugs of Antifa and the pugnacious unmasked brawlers of the right, the Proud Boys. We can look to college campuses as well for evidence of the flourishing eagerness of students to shout, shove and kick those who voice views they consider offensive. As the ethic of free speech shrivels in academe, the resort to violence creeps ever closer. Anger and violence are yoked but perhaps not as close as it often seems. Most of us, most of the time, deal with anger, just as Mrs March did in Little Women. We learn that giving voice to it hurts those we love and care for, and ends up hurting ourselves as well.

Most anger doesn’t lead to violence, though it may hint at violence. Likewise, a fair amount of violence is carried out by people who aren’t overtly angry. The stone-cold killer isn’t raging out of control. His anger, if any, is deeply buried. Generally he exalts in his absolute power over life and death and his immunity from ordinary feelings of remorse. He is a superman in his mind, not an enraged fanatic.

In that sense, most of the perpetrators of mass murder are probably not to be understood as the extreme end of the angriculture.

They are rather parasites on public anger: people capable of reiterating the grievance memes of the hour and happy to paper over their psychopathic impulses by pretending to be moved by some sense of injustice.

They pose as angry but they are really moral vacuums seeking identity as mass killers. Connor Betts, the Dayton shooter, was an Antifa supporter and far-left activist; Patrick Crusius, the El Paso shooter, ranted about immigrants and the environment; Santino Legan, the Gilroy shooter, appears to have had some connection to neo-Nazis. What stands out is that they were social losers whose attractions to extremist ideologies were window dressing in lives bereft of real purpose.

For too many Americans, anger has become the default emotion. We should recognize this, however, as a particular historical moment. It wasn’t always this way, and it won’t last forever.

We are in an age of anger — the Gilded Rage — that embodies the breakdown of older social norms for which we have as yet no compelling substitutes. New anger was distilled by the cultural left over several generations but bottled and sold to the cultural right, first through talk radio and eventually through Trump. The left’s attack on ‘angry white men’ as the source of the nation’s animosities misses the mark. Those white men, in one of the left’s fashionable words, ‘appropriated’ the style of vituperative grievance from the norm-breakers of the left, going all the way back to Allen Ginsberg telling America in 1956: ‘Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb.’

To be sure, we have plenty of other poets — the Richard Wilburs and Anthony Hechts of the same era — who spoke in the older idioms of self-control and elegant respect for others. But Ginsberg is the poet laureate of New Anger and the temperament that celebrates ‘tearing a new one’ in the other guy as the height of self-actualization and verbal dexterity.

Proud-of-itself anger is now, unfortunately, a dominating presence in our national life: a permission slip to treat others rudely and to spew contempt on the innocent if we believe we are acting on some higher principle such as ‘social justice’.

This speaks to a profound confusion in the country about what’s important and what it means to be a citizen of a self-governing republic. When our ability to govern our everyday selves by stilling our worst impulses disintegrates, our capacity to participate in governing others collapses too. New Anger’s foray into politics accounts for the wild acrimony among those who would prefer tearing the country apart to making peace with having lost an election.

This is a cultural descent for America. We have always had a vulgar side, but it was for most of our history checked and reined in by our sense of what is due to others around us. New Anger has loosened the reins. We now feel free to roar our irritation at one and all. Including Mister Softee.

This article is in The Spectator’s October 2019 US edition.