Can the European Union afford to snub Qatar? The corruption scandal engulfing the European Parliament centers around allegations that the Gulf state gave bribes in exchange for influence and favor. But if the EU cleans up this problem by distancing itself from Qatar, it might have a serious, potentially even larger, dilemma on its hands.

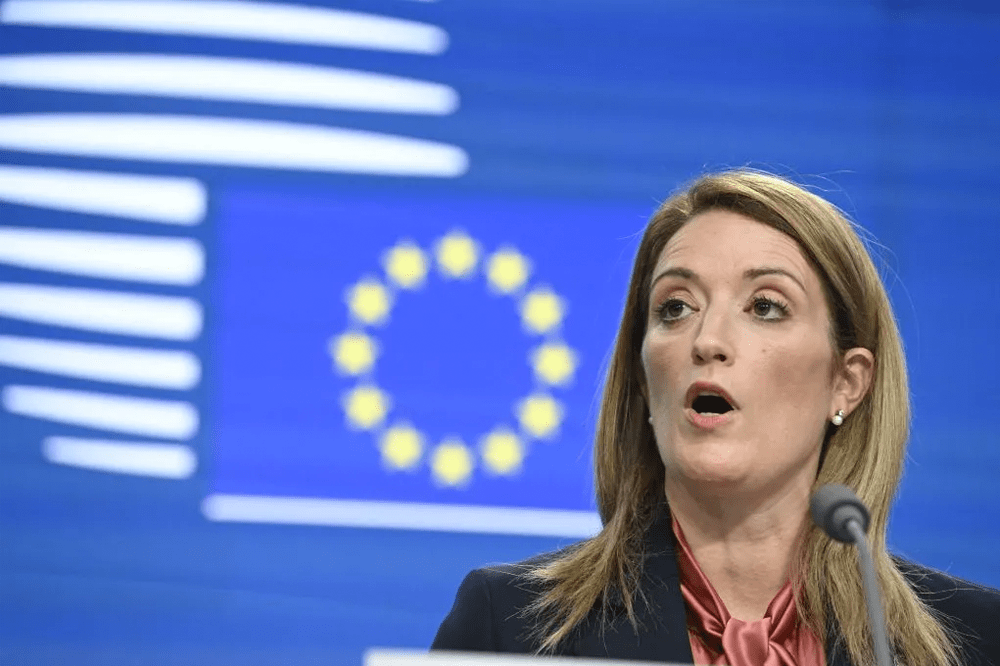

The war in Ukraine, sky-high inflation, the energy crisis and internal divisions have already shaken the very foundations of the EU. With four suspects, including Eva Kaili, a vice president of the European Parliament, now being held on charges of corruption and money laundering, what has been dubbed “Qatargate” may push the EU over the brink. Even if it wanted to, can it clean up its own act?

Before the war in Ukraine, the EU imported 40 percent of its gas and 27 percent of its oil from Russia. These gas imports have now fallen to under 10 percent with oil imports to follow by the end of the year. The resulting rise in energy prices has been a key driver of inflation, as well as making bills unaffordable for many businesses and private households. To fill the hole left by Russian gas, Europe will need to source an estimated 200 million tons of liquefied natural gas, or LNG, alone over the next few years.

What Europe needs, Qatar has. This year, it became the world’s top LNG exporter this year. It has ambitions to also become “one of the largest, if not the largest, LNG trader in the world,” as the country’s energy minister Saad al-Kaabi boasted in a recent interview.

But while the Gulf state will have a lot of energy to sell, it doesn’t rely on the EU as a market. Its biggest customers are currently China, India and Japan. Indeed, it has just signed a new twenty-seven-year deal with Beijing.

Under the circumstances, a European clean-up that risks burning bridges to Qatar is difficult to contemplate. Germany, in particular, has begun to negotiate long-term agreements with Qatar in order to make up for the lost imports from Russia. Energy minister Robert Habeck wants more: “Fifteen years is great,” he said, but “I wouldn’t have anything against twenty-year or even longer contracts.”

The catch, of course, is that Qatar is likely to want more than money in exchange for committing its oil and gas. It wants influence and easier access to the EU.

However, with the EU corruption scandal shaking Brussels to the core, the ties between the EU and Qatar are already beginning to unravel. The European Parliament voted last week to suspend “all work on legislative files relating to Qatar” and even called for Qatari officials to be barred from entering its premises.

The backlash was immediate. One Qatari diplomat threatened that the move would “negatively affect regional and global security cooperation, as well as ongoing discussions around global energy poverty and security.”

But ignoring Qatargate in the hope that such appeasement will lead to favorable energy deals is not an option either. Such a move risks driving tension within the bloc to breaking point.

The EU recently suspended €6.3 billion ($6.7 billion) in budget funds meant for Hungary over ongoing corruption concerns. While this was a compromise that means Viktor Orbán will still receive reduced funding for post-pandemic recovery, the EU has attached conditions to this that compel Budapest to implement anti-corruption measures. Enforcing this will be difficult while Brussels is dealing with the same problem.

But Hungary is not the only problem state the EU has to find a way of contending with. Qatargate raging through the very heart of the bloc itself means Brussels will find it increasingly difficult to direct its member states’ internal affairs on moral grounds. Anything less than a thorough and transparent process to deal with the corruption scandal plays into existing populist and anti-EU sentiment flourishing in some member states.

France’s Marine Le Pen, for instance, complained on Twitter that her Front National party was called out for borrowing €9 million ($9.5 million) from a Russian bank while “Qatar was delivering suitcases full of cash to all these corrupt people who are on the so-called ‘good side’.” Poland’s prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki, too, has already begun to use the EU’s dilemma to his own political advantage, calling on Brussels to “clean up its own mess” before “lecturing member states.”

Qatargate hasn’t caused the deep cracks in the EU’s foundation. But it has shone a glaring light into them. Overreliance on Russian energy, rifts between Brussels’s liberal ideology and individual member states’ aversion to it, the unaccountability of its bureaucrats — none of that is new. But the scale of problems that 2022 has exposed is.

The tinderbox of crises the EU now sits on won’t take much to ignite. Brussels now has a full-time job on its hands keeping the spark that is Qatargate away from it.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.