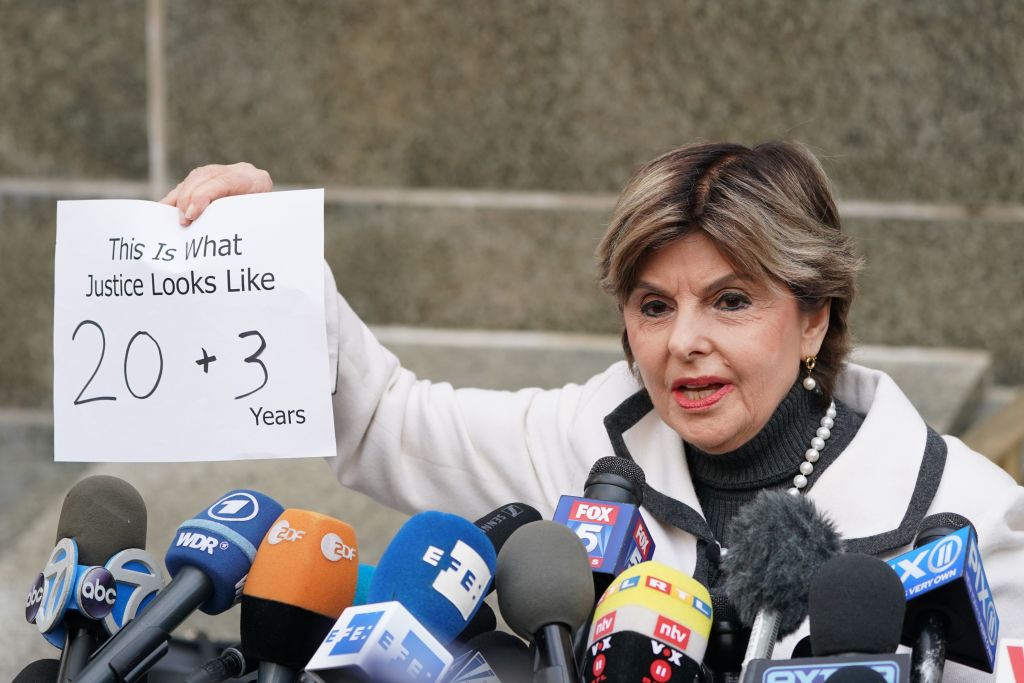

The guilty verdict in the Harvey Weinstein trial was greeted by many on the left as a great victory, overlooking the fact that Weinstein was a longstanding supporter of Hillary Clinton and one of the Democratic party’s major donors. But was it a vindication of the #MeToo movement? Yes, undoubtedly, although that’s not necessarily an unqualified triumph for justice.

If you were one of those celebrating Weinstein’s comeuppance, spare a thought for Mike Tunison. In October 2017, he was one of more than 70 people included on the ‘Shitty Media Men’ list, a compendium of anonymous allegations of sexual misconduct and assault. Tunison was accused of ‘harassment’, ‘stalking’ and ‘physical intimidation’. His career at that point was in high gear: he had worked for the Washington Post, been editor-in-chief of an NFL-related humor blog called Kissing Suzy Kolber, and published a book with HarperCollins. After the allegations appeared, it ground to a halt.

As he confessed in a heartbreaking piece for Medium earlier this year, he now can’t get work as a journalist. Indeed, he’s teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and worried about losing his one-bedroom condo. He’s never been through anything resembling due process, let alone a trial. He was just assumed to be guilty on the basis of a single, unsourced document that was taken down from the internet after 12 hours.

‘It’s been more than a year since I’ve dated,’ he wrote. ‘Working three low-paying jobs means I’m always busy — and broke. Plus, any woman who does the usual predate research online could stumble upon the list. How could I explain it away in the early stages of a relationship?’

When Tunison was pulled over and ticketed recently because he couldn’t afford to get the inspection tags on his car renewed, he was reduced to begging his Twitter followers for help. At that point, Stephen Elliott, another victim of the Shitty Media Men list, stepped in and started a crowdfunding page to help get Tunison back on his feet. Elliott’s career was so damaged by his inclusion on the list — he was accused of rape by an anonymous contributor — that he came close to committing suicide. But he’s now put his life back together and is suing Moira Donegan, who created the original McCarthyite document.

In the 12 months that followed the original allegations against Harvey Weinstein in 2017, at least 429 prominent people across a range of industries were publicly accused of sexual misconduct, according to Bloomberg (the news organization, not the erstwhile Democratic presidential candidate, who has his own #MeToo problems). No doubt some of them were guilty as charged, but in the majority of cases we have no idea because so few of them went to trial.

Then as now, the reaction of most men facing a #MeToo complaint is to keep their heads down and say nothing in the hope that the outrage caravan will move on, or, if they’re lucky enough to have some employment rights, sign a severance agreement. Few have the intestinal fortitude to challenge their accusers, knowing they’ll face a chorus of ‘believe survivors’.

When #MeToo cases do go to court, the verdict isn’t always guilty. Earlier this year, Universal Pictures was ordered by a judge to pay its former marketing chief Josh Goldstine $20 million, after dismissing him in 2018. Needless to say, when his accusers first came forward, the studio brass issued a memo saluting them for their ‘courage’.

The memo continued: ‘We have no tolerance for harassment or other disrespectful behavior, and we will be taking any necessary steps to ensure that actions that violate our core values are dealt with swiftly and decisively.’ Don’t the studio’s ‘core values’ include believing a man to be innocent until proven guilty? I probably don’t need to remind you that Universal was not the studio that made 12 Angry Men.

I experienced my own version of this when I was targeted by a digital outrage mob at the beginning of 2018. My sin was having been appointed to the board of a new higher education regulator by the then-British prime minister, which immediately prompted an army of offense archaeologists to start sifting through everything I’d said or written dating back to 1987. Because they found a few tweets about celebrities’ breasts, people would often accompany their condemnation of me with the hashtags #MeToo or #TimesUp. As far as they were concerned, I was morally indistinguishable from Weinstein, even though I’ve never been accused of sexual harassment or assault (not even anonymously). During the tsunami of outrage whipped up by the Weinstein exposé, all male, pale and stale conservatives were assumed to be sexual predators, even happily married fathers of four.

Actually, the word ‘pale’ doesn’t belong in that sentence. African American men are more likely to be wrongfully charged with rape than white men, and several of the high-profile figures brought low by a #MeToo scandal in the past 12 months have been black. I’m thinking, for instance, of Roland Fryer, the Harvard economist who was suspended last year following a threadbare Title IX complaint and of Ronald Sullivan, the Harvard Law professor whose tenure as dean of Winthrop House was cut short after he joined Harvey Weinstein’s defense team. For Harvard to punish one black professor on a flimsy #MeToo pretext may be regarded as a misfortune; to punish two looks like carelessness — as Wilde might have had it.

When reflecting on the Weinstein verdict, remember that ‘social justice’ isn’t justice. One man may have gotten what he deserves, but the guilty verdict will lead to hundreds more being falsely accused.

This article is in The Spectator’s April 2020 US edition.